I've brought up stories and commentary before about white people who consume reggae, a historically black musical genre (I totally fall under the category of white people who consume reggae). Now I'd like to complicate things a little by talking about white producers, rather than consumers, of reggae. In order to do this, I'd like to examine three (primarily) white bands that have played reggae, or at least reggae-influenced music: The Police, UB40, and The Aggrolites.

First, lets look at the Police. While I'll acknowledge that Stuart Copeland is an awesome drummer, Sting's fake Jamaican accent has always annoyed the shit out of me. Let's listen to an example:

While The Police were never really a reggae band by definition, the song "Walking on the Moon" is one of the best examples of the massive reggae-influence on their music, which can also be heard in Sting's vocals. For their first few albums, Sting put on a ridiculous fake Jamaican-style accent (he never really got it right), presumably to try and imitate the Jamaican Patois heard in many reggae songs. The thing that's always amazed me though is that Sting really really overcompensated. Let's listen to a song by Jimmy Cliff to compare:

Notice anything different? I've been in linguistics classes where we've examined Jamaican Patois, and one thing we've noticed is that Jimmy Cliff doesn't really use it in his songs. The same goes for a lot of other reggae singers. In the music of the Police, however, Sting makes a huge effort to put on a Jamaican accent. The other thing to note is that Sting phased out the fake accent later in his career, but by this point the Police were playing a lot of other stuff besides reggae-influenced-pop. Basically the point I'm trying to make is that in the reggae music of the Police, Sting used a fake Jamaican accent as a signifier of reggae, even though he really didn't need to, since Jimmy Cliff didn't, and he's one of the best reggae singers of all time.

So, to reference a question raised by scholar Terry Boyd in relation to hip hop, is the music of the Police an imitation of reggae, or is it influenced by reggae? Well, the answer is both. They're not mutually exclusive. I kind of think that to an extent one implies the other, and you'll noticed that I've already used both words in describing The Police. The point, however, is that, to an extent at least, the music of the Police WAS an imitation, since Sting pretty blatantly imitated Jamaican English, which he at least saw as a major signifier of reggae.

On to the next example: UB40. The two things that really really separates them from The Police are that

1. They were obviously a reggae band, and

2. They were an even more blatant imitation

I'm not even gonna try and defend their music, since it was almost 100% imitation, rather than influence. Seriously, they became famous just by covering reggae songs that were already hits in Jamaica. The album that made them famous, Labour of Love, is all covers. I've listened to every song on that album, and I've listened to the original versions of every song on that album, and in every case the original is better. Actually that's just a matter of opinion for me, but my point about UB40 is that they fall under the category of imitation rather than influence, since they made massive amounts of money by literally imitating reggae songs that had already been played by less successful people. And their lead singer, who was also white, also sang in a fake Jamaican accent. I would go so far as to call UB40 the Elvis of reggae.

Anyway, let's move on to my last example: The Aggrolites. They're even more noticeably different from the other two examples, because:

1. They're American

2. They're not as popular

3. They play a very different style of reggae

4. They don't put on ridiculous accents

The last point is reason enough to believe that the Aggrolites fall less under imitation and more under influence. But the other thing that makes the Aggrolites stand out for me is that, unlike The Police and UB40, who use fake Jamaican accents as a reggae signifier, The Aggrolites use something very different as a signifier: the skinhead image. Just to provide some background, the skinhead subculture originally emerged in England in the 1960s and was in no way affiliated with Neo-Nazis. While the original skinheads did exhibit racism towards Indian and Pakistani immigrants, they showed solidarity towards Jamaican immigrants, and were huge fans of reggae and ska. As a result, some reggae bands, most notably Syramip, began targeting their music towards skinheads, most obviously in the song "Skinhead Moonstomp."

Now listen to this song by the Aggrolites and compare it to the Jimmy Cliff song and the Syramip song:

This one is obviously more influenced by Syramip than Jimmy Cliff; the tempo is almost exactly the same, the production is just as minimal, and the vocals are shouted and chanted rather than sung. I've also seen The Aggrolites live, and they performed Skinhead Moonstomp. Basically, The Aggrolites choose to use the skinhead subculture as a reference point for the reggae that they play. This choice is still problematic, no question. But they're not pretending to be Jamaican. There are two factors at play in this. For one, by referencing skinheads the Aggrolites show a familiarity with the history of reggae. The Police and UB40 just put on fake accents as an obvious way of saying "This is reggae," but the Aggrolites choose instead to reference an aspect of reggae that people might not be as familiar with, showing their familiarity with the music. It should also be noted that while The Police and UB40 played music that had all the surface elements of reggae as a way to make money, the Aggrolites have played a different type of reggae and not been as successful. The second factor at play is that by referencing the skinhead subculture, it could be argued that The Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as outsiders of reggae. While not all of The Aggrolites are white, not all skinheads were white either, and by referencing skinheads rather than trying to sound Jamaican, the Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as consumers of reggae and not pretending to be the original producers of it. Both strategies are ways to claim authenticity, but the strategy the Aggrolites employ is one that acknowledges their outsider status.

So to return to that question again, do the Aggrolites imitate reggae, or are they influenced by it? Again, the answer is both. The two aren't mutually exclusive, and I think it's almost impossible for them to be entirely separate. But since, by referencing skinheads rather than just putting on fake accents, the Aggrolites have engaged with the history of reggae and also acknowledged their status as outsiders in reggae, I'd say they fall more under the category of influence.

Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Don't Believe The Hype: A Criticism of Criticisms of Rap

"Every generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it." – George Orwell

"Although American rap music has been used as a vehicle for the creation of novel indigenous musical styles (in South Africa), it has come under heavy criticism from the older generation of South African musicians, some of whom have dismissed indigenous rap as hopelessly imitative of the worst excesses of American culture…. South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela complained that 'our children walk with a hip hop walk and they think they are Americans….' Ironically, the jazz music Masekela… pioneered owed an equal debt to American jazz artists as kwaito does to American rap. Furthermore, Black jazz musicians of the 1950s were subject to similar criticisms by the cultural elite." – Zine Magubane, "Globalization and Gangster Rap."

"The Arabic hip hop genre has faced strong resistance from various cultural forces. Abbas, who traces the development of this genre across the Arab world, argues that this resistance was not necessarily the result of musical evaluation, but rather a natural reaction to anything that sounds western as well as the response of people who feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." – Usama Kahf, "Arabic Hip Hop"

"Those interested in black music and black politics should check out studies on the racial uplift ideology literature of the late 19th Century through 1950s, which reveals, among other things, “New Negro” discomfort with black folk culture (demonstrative church music, blues, jazz, narratives depicting uneducated black folk.). This literature features recurring questions such as “How does popular black art affect the moral training of black children?” and “How will this art make us look to white people?” If you replace all of the “negro”s with “black”s or “African American”s,” you’d swear that these things were written today." – Gordon Gartrelle "The Problem With These Rap Critics Today"

"No question. Rap is the repetition of the minstrel show." – Wynton Marsalis

I know I'm just listing quotes, but that's because the quotes speak for themselves.

If you can't tell already, the aim of this post is to examine some of the most prominent criticisms of rap music. In some ways, these quotes contradict the points that I made in my earlier post about de-politicization. In that post, I discussed how white cultural critics have often criticized black musical forms because of their political aspects. But, as I noted, white critics have never been the only ones to criticize new black (or) political musical forms. As you can see, South African jazz musicians have criticized South African rap, Arabic hip hop has faced criticism in local communities, and Wynton Marsalis, a prominent black jazz musician, has been an incredibly vocal critic of hip hop.

What really amazes me is how almost universal these criticisms are. It seems that no matter what context hip hop is created in, there are always vocal critics of it who attack it using countless different arguments. A lot of these criticisms are valid; lots of feminist thinkers, for example, have rightly noted that a lot of hip hop contains deeply misogynist lyrics. But I think the key phrase in statements like this that makes them valid is "a lot of hip hop." The problem I have with criticisms such those of Marsalis is that they are sweeping generalizations that don't allow any room for exceptions. To label an entire musical form as "the repetition of the minstrel show" is a deeply problematic easy way out. Plus, a lot of these criticisms seem to be representative of an unwillingness to accept new musical forms.

One common thread that seems to lie behind all these criticisms of rap is a desire to hold on to tradition. This ties in to Kahf's quote about how many people "feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." This argument can even be applied to my discussion of musical de-politicization (sorry to reference myself, but I do think it's relevant). The fact that lots of white cultural critics have criticized political black musical forms can easily be read as a desire to hold on to a tradition of power, since these critics feel threatened by hip hop. The critics discussed in the pieces by Magubane and Kahf can also be seen as feeling threatened by other political aspects of hip hop. Globalization is a powerful force, and the United States are one of the most influential countries globally; I observed this first hand while traveling this summer. While hip hop can be used in local communities as a tool of resistance, it still has ties to America, since it is historically an American musical form. This is another way in which people probably feel threatened by hip hop; American media can be seen in lots of different countries, and people who have this media imposed on them may understandably reject American musical forms that can even be used subversively. We can even read Wynton Marsalis's criticism as being a reaction to the threat that Jazz has faced from hip hop, which is a far more popular genre among young people today.

I'd like to discuss Marsalis's statement a little bit more, and why I feel it is so deeply problematic. Lots of people have proposed the "hip hop is minstrelsy" argument before, but some people, such as Jeffrey Ogbar, author of the book Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap, have taken a better approach to it. The problem I have with Marsalis's argument as opposed to Ogbar's is that while Marsalis condemns the entire form of hip hop, Ogbar makes a clear distinction between hip hop he sees as being a reprisal of the minstrel show, and hip hop that he views otherwise. In addition, he also provides historical context on both minstrelsy and hip hop. I don't have a problem with criticizing hip hop, as long as you don't dismiss the entire form, and as long as you back up your ideas without making sweeping claims.

I'll also add that the issue of holding on to tradition vs. accepting globalized music is a really complicated one, and I'm not trying to make it seem like the people who criticize hip hop in a global setting are wrong, since I really don't know enough about the specific contexts. I'm just pointing out that a lot of criticisms of hip hop come out of the same desire to hold on to tradition.

"Although American rap music has been used as a vehicle for the creation of novel indigenous musical styles (in South Africa), it has come under heavy criticism from the older generation of South African musicians, some of whom have dismissed indigenous rap as hopelessly imitative of the worst excesses of American culture…. South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela complained that 'our children walk with a hip hop walk and they think they are Americans….' Ironically, the jazz music Masekela… pioneered owed an equal debt to American jazz artists as kwaito does to American rap. Furthermore, Black jazz musicians of the 1950s were subject to similar criticisms by the cultural elite." – Zine Magubane, "Globalization and Gangster Rap."

"The Arabic hip hop genre has faced strong resistance from various cultural forces. Abbas, who traces the development of this genre across the Arab world, argues that this resistance was not necessarily the result of musical evaluation, but rather a natural reaction to anything that sounds western as well as the response of people who feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." – Usama Kahf, "Arabic Hip Hop"

"Those interested in black music and black politics should check out studies on the racial uplift ideology literature of the late 19th Century through 1950s, which reveals, among other things, “New Negro” discomfort with black folk culture (demonstrative church music, blues, jazz, narratives depicting uneducated black folk.). This literature features recurring questions such as “How does popular black art affect the moral training of black children?” and “How will this art make us look to white people?” If you replace all of the “negro”s with “black”s or “African American”s,” you’d swear that these things were written today." – Gordon Gartrelle "The Problem With These Rap Critics Today"

"No question. Rap is the repetition of the minstrel show." – Wynton Marsalis

I know I'm just listing quotes, but that's because the quotes speak for themselves.

If you can't tell already, the aim of this post is to examine some of the most prominent criticisms of rap music. In some ways, these quotes contradict the points that I made in my earlier post about de-politicization. In that post, I discussed how white cultural critics have often criticized black musical forms because of their political aspects. But, as I noted, white critics have never been the only ones to criticize new black (or) political musical forms. As you can see, South African jazz musicians have criticized South African rap, Arabic hip hop has faced criticism in local communities, and Wynton Marsalis, a prominent black jazz musician, has been an incredibly vocal critic of hip hop.

What really amazes me is how almost universal these criticisms are. It seems that no matter what context hip hop is created in, there are always vocal critics of it who attack it using countless different arguments. A lot of these criticisms are valid; lots of feminist thinkers, for example, have rightly noted that a lot of hip hop contains deeply misogynist lyrics. But I think the key phrase in statements like this that makes them valid is "a lot of hip hop." The problem I have with criticisms such those of Marsalis is that they are sweeping generalizations that don't allow any room for exceptions. To label an entire musical form as "the repetition of the minstrel show" is a deeply problematic easy way out. Plus, a lot of these criticisms seem to be representative of an unwillingness to accept new musical forms.

One common thread that seems to lie behind all these criticisms of rap is a desire to hold on to tradition. This ties in to Kahf's quote about how many people "feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." This argument can even be applied to my discussion of musical de-politicization (sorry to reference myself, but I do think it's relevant). The fact that lots of white cultural critics have criticized political black musical forms can easily be read as a desire to hold on to a tradition of power, since these critics feel threatened by hip hop. The critics discussed in the pieces by Magubane and Kahf can also be seen as feeling threatened by other political aspects of hip hop. Globalization is a powerful force, and the United States are one of the most influential countries globally; I observed this first hand while traveling this summer. While hip hop can be used in local communities as a tool of resistance, it still has ties to America, since it is historically an American musical form. This is another way in which people probably feel threatened by hip hop; American media can be seen in lots of different countries, and people who have this media imposed on them may understandably reject American musical forms that can even be used subversively. We can even read Wynton Marsalis's criticism as being a reaction to the threat that Jazz has faced from hip hop, which is a far more popular genre among young people today.

I'd like to discuss Marsalis's statement a little bit more, and why I feel it is so deeply problematic. Lots of people have proposed the "hip hop is minstrelsy" argument before, but some people, such as Jeffrey Ogbar, author of the book Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap, have taken a better approach to it. The problem I have with Marsalis's argument as opposed to Ogbar's is that while Marsalis condemns the entire form of hip hop, Ogbar makes a clear distinction between hip hop he sees as being a reprisal of the minstrel show, and hip hop that he views otherwise. In addition, he also provides historical context on both minstrelsy and hip hop. I don't have a problem with criticizing hip hop, as long as you don't dismiss the entire form, and as long as you back up your ideas without making sweeping claims.

I'll also add that the issue of holding on to tradition vs. accepting globalized music is a really complicated one, and I'm not trying to make it seem like the people who criticize hip hop in a global setting are wrong, since I really don't know enough about the specific contexts. I'm just pointing out that a lot of criticisms of hip hop come out of the same desire to hold on to tradition.

Posted by

Jake

Sunday, November 8, 2009

5:00 PM

Samurai Spirit: Orientalist Images of Japan in Contemporary Film

In her piece "Black Bodies/Yellow Masks," Deborah Elizabeth Whaley identifies four different Orientalist images that are commonly found in popular culture:

"(1) the sexualized, yet virginal Japanese geisha; (2) the South Asian Indo-chic; (3) the Chinese kung fu warrior; and (4) the use of Asian languages as an iconographic fashion statement detached from specificity of meaning and etymological usage."

While these images are important to recognize in popular culture, I also think that Whaley's list comes dangerously close to equating Japan with femininity and China with masculinity. That's why I want to concentrate on #3 in this post, specifically because "the Chinese kung fu warrior" definitely has a Japanese counterpart: the Samurai.

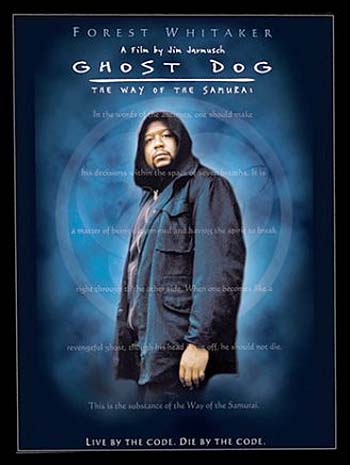

Many people have noted the Orientalist aestheics in the music and imagery of the Wu-Tang Clan. When looking at Whaley's list, it's obvious that the primary image used by the Wu-Tang Clan is #3. This is one reason why I'm using the image of the samurai as a parallel to the "kung fu warrior." The RZA, a member of the Wu-Tang Clan, has composed the score for two movies that I must admit I'm fond of, but that I also must admit show very orientalist images of samurai: Afro Samurai and Ghost Dog. These movies are also good reference points for discussing the same relationships between African American culture and Asian culture that Whaley discussed in her piece.

For this post, I'm going to specifically focus on Ghost Dog, since I've seen it way more times. This movie features Forrest Whitaker (one of a few famous alums of my high school), as a hit man whose entire personal philosophy is based on Hagakure, an 18th century book by Yamamoto Tsunetomo that outlines the code of the samurai. The one thing I will say in the film's defense is that it's based on an actual book, and it would've been way easier for the writers to just make stuff up. Still, the fact that the movie derives almost all of its imagery from this book is problematic. While Whaley is very positive about the use of Asian imagery in African American art, and while the issue is undoubtedly a very complex one, images like these can still be used to produce an essentiallized image of Asia.

It's nothing new for images of samurai to be used in Orientalist ways. Much like the belly dancing discussed in Susaina Maira's piece entitled "Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire," representations of a "samurai code" can be a way to profess an interest in Japan while avoiding discussions of contemporary issues that Japanese people actually face. I spent last semester in Japan, and the only time I was ever involved in a discussion that had anything to do with samurai philosophy was in an art history course, and even then it was only as a small part of one class. But there are still American songs, films, and people that base all their knowledge of Japan on romanticized ideas of the samurai.

I'm reminded of a scene in a movie I just watched called "Kamome Shokudo," which is about three Japanese women who work in a Japanese restaurant in Finland. In the movie, there is a young male Finnish character named Tommi who starts coming to the restaurant because, like many young white males including myself, he has an interest in Japanese culture. In almost every scene that this character is in, he is wearing a shirt that has some representation of Japanese culture, most of which are from contemporary Japanese popular culture (this description might sound eerily familiar for people who know me). Most of the time, the women who work in the restaurant either make some friendly comment about his shirt or don't make a comment about it at all. The only scene in which any of the women have a noticeably different reaction to one of his shirts is when he is wearing one that has the kanji for "samurai spirit" on it. In the beginning of the movie, he wears a shirt with a Japanese cartoon character, and one of the women in the restaurant is able to relate to it. But the woman who comments on the "samurai spirit" shirt is portrayed as being unable to relate to it. I think these scenes are pretty good representations for a number of reasons. Tommi's character is not really portrayed as being Orientalist, and his shirts display a wide range of Japanese cultural artifacts. But the only shirt he wears that is portrayed as being Orientalist is the one that conveys a dated, romanticized notion that doesn't have as much relevance in contemporary Japanese society. This also ties in to #4 on Whaley's list: " the use of Asian languages as an iconographic fashion statement detached from specificity of meaning and etymological usage."

One more thing that I'll comment on is the fact that Chinese and Japanese cultures can be (sometimes inadvertently) portrayed as interchangeable in popular culture. I'm not going to get into this in too much detail, but I do find it interesting that the RZA, a producer who derives much of his aesthetics from Chinese popular culture, did the score for two movies that derive much of their imagery from Japanese culture. This is just one reason why I think that the image of the samurai can be viewed as a counterpart to "the Chinese kung fu warrior."

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, October 31, 2009

5:51 PM

Musical De-Politicization, Nostalgia, and Moral Outrage

I'd like to continue and elaborate on some of the points I made in my piece about canonization.

In Kevin Phinney's piece "Souled American" there was a quote that really caught my attention:

"African Americans are more interested in discovering the Next Big Thing than in riding a fad past its relevance to daily life. Certainly there's no reason for black Americans to romanticize their experience here. This country hasn't provided any good old days for people of color."

Phinney then went on to discuss how white people "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo," and compared "white music" to "an old lamp," referring to its sentimentality and nostalgia. While I do think this is a bit of an over-generalization, I also think there is some truth to it. To understand why, it is important to discuss the ways in which black musical forms have political origins.

Many, many historically black musical forms have been political in some way. Rap is an obvious example, and it's also very easy to hear political sentiment expressed in reggae, soul, and even largely instrumental musical forms like jazz. And in all of the musical forms listed above, race plays a hugely important role in the musical politics. From Louis Armstong's "Black and Blue" to Curtis Mayfield's "Don't Worry (If There's a Hell Below)" to The Abbyssinians' "Black Man's Strain" to Public Enemy's "Fight The Power," countless black musicians have used music as a way to challenge racism and oppression. And these musicians have often received incredibly harsh criticism for doing so.

Many articles about pop music discuss the initial reaction of many white people to black musical forms. Nick Bromell, in his piece "The Blues and the Veil," discussed the negative reaction to early rock music, and Phinney does as well, in addition to discussing the reactions many whites have had to rap music. Many white cultural critics have dismissed rock as well as rap in the name of "morals," condemning these musical forms as being too sexual and immoral. It is completely possible to read these criticisms as being reflective of stereotypes that equate blackness with sexuality, and while I definitely think that argument is true, I also don't think it's the only factor involved. I would like to argue that these negative, racist responses are also a reaction to the political aspects of these musical forms, whether they are explicit or implicit.

I'd like to go back to the Phinney quote about how white people can "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo." Both rock and rap have threatened the status quo of white political power. With rap it's easy to see why; many of the most popular and influential rap songs have lyrics that are directly, explicitly critical of white hegemony. While the lyrics of early rock songs were in no way as explicitly political, there was still a political aspect to the popularity of rock music. Like jazz before it, rock was an originally black musical form that became popular among white people, which in itself threatened the white status quo (even though white people combated this by elevating Elvis to his popularity). It makes sense that the conservative (and sometimes liberal) white people who criticize(d) these musical forms would do so as a reaction to their threatened status quo, even if they used other reasons to justify their criticism. To phrase it differently, many of the white cultural critics who condemn black musical forms are afraid of the popularity of these forms and want to hold on to their power.

But where does nostalgia fit in to this discussion? Phinney also discussed how there has been a historical pattern of black people innovating a musical form and white people profiting off of it. While many black musical forms have had political origins, these forms have often lost their explicitly political meaning in the eyes of white America when they have been appropriated and turned mainstream. When music challenges whiteness it is obviously hard for white people to listen to it, and many white people have intense reactions to it. But when it is appropriated, transformed, and marketed to a new audience, it loses much of its political potency. Jazz and rock were originally condemned by the mainstream media, but are now part of it. And this is where I feel nostalgia plays a role.

Many people who have condemned rap music have also referenced the "good old days" of jazz or rock, completely unaware of their hypocrisy. I'd like to argue that the reason many white people are fixated on the "good old days" has everything to do with power. When rap started to come under fire from the mainstream media, rock and jazz had already been de-politicized. The "good old days" were referenced because there was a desire to hold on to music that had less political power than it used to, and less political power than more contemporary musical forms that had not been de-politicized. Again, we can see history repeat itself. When looking at music from a historical perspective, we can see a pattern that goes something like this:

Innovative and sometimes explicitly political black music becomes popular

A lot of white people condemn this new music (although white people are not always the only ones who do so)

This music is appropriated, commercialized, and de-politicized by other white people (as in the case of Elvis or Clapton)

Said music becomes mainstream

A new form of music appears, and the process repeats itself, with people lamenting the waning popularity of the music that used to be political and hated

To quote Stuart Hall, "This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion; the year after, it will be the object of a profound cultural nostalgia." You could also add "then it will be referenced in opposition to a new radical form."

In Kevin Phinney's piece "Souled American" there was a quote that really caught my attention:

"African Americans are more interested in discovering the Next Big Thing than in riding a fad past its relevance to daily life. Certainly there's no reason for black Americans to romanticize their experience here. This country hasn't provided any good old days for people of color."

Phinney then went on to discuss how white people "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo," and compared "white music" to "an old lamp," referring to its sentimentality and nostalgia. While I do think this is a bit of an over-generalization, I also think there is some truth to it. To understand why, it is important to discuss the ways in which black musical forms have political origins.

Many, many historically black musical forms have been political in some way. Rap is an obvious example, and it's also very easy to hear political sentiment expressed in reggae, soul, and even largely instrumental musical forms like jazz. And in all of the musical forms listed above, race plays a hugely important role in the musical politics. From Louis Armstong's "Black and Blue" to Curtis Mayfield's "Don't Worry (If There's a Hell Below)" to The Abbyssinians' "Black Man's Strain" to Public Enemy's "Fight The Power," countless black musicians have used music as a way to challenge racism and oppression. And these musicians have often received incredibly harsh criticism for doing so.

Many articles about pop music discuss the initial reaction of many white people to black musical forms. Nick Bromell, in his piece "The Blues and the Veil," discussed the negative reaction to early rock music, and Phinney does as well, in addition to discussing the reactions many whites have had to rap music. Many white cultural critics have dismissed rock as well as rap in the name of "morals," condemning these musical forms as being too sexual and immoral. It is completely possible to read these criticisms as being reflective of stereotypes that equate blackness with sexuality, and while I definitely think that argument is true, I also don't think it's the only factor involved. I would like to argue that these negative, racist responses are also a reaction to the political aspects of these musical forms, whether they are explicit or implicit.

I'd like to go back to the Phinney quote about how white people can "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo." Both rock and rap have threatened the status quo of white political power. With rap it's easy to see why; many of the most popular and influential rap songs have lyrics that are directly, explicitly critical of white hegemony. While the lyrics of early rock songs were in no way as explicitly political, there was still a political aspect to the popularity of rock music. Like jazz before it, rock was an originally black musical form that became popular among white people, which in itself threatened the white status quo (even though white people combated this by elevating Elvis to his popularity). It makes sense that the conservative (and sometimes liberal) white people who criticize(d) these musical forms would do so as a reaction to their threatened status quo, even if they used other reasons to justify their criticism. To phrase it differently, many of the white cultural critics who condemn black musical forms are afraid of the popularity of these forms and want to hold on to their power.

But where does nostalgia fit in to this discussion? Phinney also discussed how there has been a historical pattern of black people innovating a musical form and white people profiting off of it. While many black musical forms have had political origins, these forms have often lost their explicitly political meaning in the eyes of white America when they have been appropriated and turned mainstream. When music challenges whiteness it is obviously hard for white people to listen to it, and many white people have intense reactions to it. But when it is appropriated, transformed, and marketed to a new audience, it loses much of its political potency. Jazz and rock were originally condemned by the mainstream media, but are now part of it. And this is where I feel nostalgia plays a role.

Many people who have condemned rap music have also referenced the "good old days" of jazz or rock, completely unaware of their hypocrisy. I'd like to argue that the reason many white people are fixated on the "good old days" has everything to do with power. When rap started to come under fire from the mainstream media, rock and jazz had already been de-politicized. The "good old days" were referenced because there was a desire to hold on to music that had less political power than it used to, and less political power than more contemporary musical forms that had not been de-politicized. Again, we can see history repeat itself. When looking at music from a historical perspective, we can see a pattern that goes something like this:

Innovative and sometimes explicitly political black music becomes popular

A lot of white people condemn this new music (although white people are not always the only ones who do so)

This music is appropriated, commercialized, and de-politicized by other white people (as in the case of Elvis or Clapton)

Said music becomes mainstream

A new form of music appears, and the process repeats itself, with people lamenting the waning popularity of the music that used to be political and hated

To quote Stuart Hall, "This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion; the year after, it will be the object of a profound cultural nostalgia." You could also add "then it will be referenced in opposition to a new radical form."

Posted by

Jake

Sunday, October 25, 2009

5:41 PM

The Problems of Canonization

In 1994, scholar Harold Bloom proposed the idea of a literary "Western Canon," a collection of works that he deemed to be under fire by a so-called "school of resentment" represented by scholars who criticized the hegemony of classical European literature. Bloom's selection of works were ones that he considered to be important solely for their aesthetic qualities, rather than their social aspects. Bloom's ideas are what Taylor would likely describe as representative of modernist ideas of aesthetics; namely, that art should exist for art's sake, for nothing else other than beauty. The fact that Bloom chose to only label western works as being beautiful is on the surface entirely antithetical to the idea that social factors have nothing to do with aesthetics, but, as scholar Timothy D. Taylor shows, the viewing of western works as the most beautiful and aesthetically perfect is entirely consistent with the modernist view of aesthetics, which Taylor argues "strips everything of history, culture, and the social." Indeed, Bloom's views that European art forms are under attack are views that entirely ignore the history of colonialism, which put said western works on a pedestal in the first place.

It is not at all surprising that Bloom is an incredibly controversial figure, and that he is viewed as an elitist by many. But even if Bloom had never materialized his reactionary views into words, the idea of a literary canon has undoubtedly existed as long as the study of western literature has. I am certainly not the first person to notice similarities between academic ideas of literary canons and contemporary ideas of musical canons. For example, music critic Jim DeRogatis made a comparison between Bloom's western canon and contemporary music canons in his book Kill Your Idols, which is largely a criticism of commonly accepted musical canons. DeRogatis notes the connection between canons and nostalgia, arguing that the negative effects of nostalgia are often what inspire the creation of canons (this argument could be applied to Bloom's canon as well). However, rather than using this argument to attack canons of traditional "European music," as many other authors have, DeRogatis applies this argument to canons of rock music, which he sees as entirely antithetical to a musical form that was originally rebellious. DeRogatis argues in Kill Your Idols that nostalgia for the 60s among baby boomers has led to the creation of a rock music canon, which includes artists such as The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Rolling Stones, and that such a canon is just as elitist as Bloom's western canon or other scholars' notions of a European music canon.

Just to provide some more context, DeRogatis's argument is basically that the unofficial rock music canon as viewed by many people consists of "classic rock" bands from the 60s and 70s who were involved in some way in the hippie movement (indeed, the very term "classic rock" itself conveys the idea of a canon). When analyzing both the "European music" canon and the aforementioned rock music canon we can see many similarities. In fact, the rock music canon that DeRogatis describes and attacks is largely a European music canon, as bands such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, and Led Zeppelin are generally viewed as the most "aesthetically perfect" bands of this canon. Furthermore, in both examples of canons we can see how hegemonic these notions truly are, and how canons are used to serve dominant social groups. With some notable exceptions (Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana), members of the classic rock canon are generally white men, as are members of the traditional "European music" canon. It could even be argued that the rock music canon is even more problematic, since much of its repertoire is derived from African American musical forms, especially in the case of Led Zeppelin, who actually covered songs by African American musicians on their albums and credited themselves as the songwriters (I'll save my rants on Led Zeppelin for another time though). But on the other hand, as Taylor notes, many romantic composers derived their works from Other musical styles as well. So the European music canon and the rock music canon really aren't a whole lot different.

I'd like to apply this argument to a quote from scholar Philip Tagg that references Jimi Hendrix. Specifically, Tagg mentions the idea of how many music scholars would "laugh when you propose a Jimi Hendrix memorial guitar scholarship or suggest a series of workshops on the accordion… or try to start a course in Country and Western ensemble playing," but then goes on to say that "quite a few white European fans of ‘Afro-American music’ reading these lines would probably approve of the Jimi Hendrix scholarship but feel less sympathy for the accordion or C&W ideas…. [This] means that the most ironical effect of the twisted view of European music has been to perpetuate the rules of a ‘better-than-thou’ game in the field of musical aesthetics, so that even those of us trying to beat the ancien [sic] regime actually end up by playing the same game as our rivals, instead of changing the rules or moving to another sport altogether." While Hendrix does stand in contrast to the mostly white rock music canon, this quote still illustrates how "classic rock" has been canonized and how this is just as hegemonic as canonizing classical or romantic music. While many people who do canonize rock music probably think that they are rebelling against hegemony, in the process they are simply creating a new form of it. This is especially true since, as stated before, members of the rock music canon are largely white. True, the canon does include Jimi Hendrix, but he is definitely an exception. Can anyone think of any other black musicians who are frequently labeled "classic rock?" None of my friends could when I asked them, and I can think of way more examples of white people who are.

There is one point of disagreement I have with the above quote, but I also think that if Tagg wrote this article today instead of in 1989 he would have written it differently. Specifically, I would like to argue that while Tagg puts country music in opposition to classical music and classic rock, recently a canon of country music has been emerging. Many contemporary musical elitists are beginning to put country music onto a pedestal, just like people did with rock music before. In fact, the people who are currently creating a country music canon probably think they are doing so as a rebellious act as well. If you don't believe my argument about country music, I'll just mention that I work as a monitor in the music building at my school and one of the genres I hear the most is bluegrass, played by students presumably because of its perceived authenticity. While the creators of this country music canon may have rebellious intentions, just as the baby boomers did before them, we can see from the latter example that canons are inherently un-rebellious, since instead of dismantling cultural norms they simply change them slightly.

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, September 26, 2009

4:27 PM

Asian Appropriation Alert: The Weapon

Found out from Angry Asian Man that up-and-coming Shia LeBouf-esque Disney channel star David Henrie will be playing an Asian guy in a movie of comic book The Weapon. To quote Angry Asian Man:

"I am not familiar with The Weapon, but from what I've read about it, Tommy Zhou is indeed an Asian character. David Henrie, who I had never even heard of before reading this news item, is not an Asian person. Hooray for Hollywood, you've done it again. That's racist!"

I also have to add that this is another case of something like Keanu Reeves in Cowboy Bebop or that guy from Across the Universe in 21. Even if we're not talking about representation, how could someone who's been compared to Shia LeBouf (is that how you spell his name? I really don't care) truly be the best actor for this part, regardless of race? Especially when the character is written to be a specific race?

Anyway, I'm still amazed by how often this is happening. And it seems like this movie is gonna suck anyway.

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, September 19, 2009

2:46 PM

Asian Appropriation Alert: King of Fighters

I heard about this one from Angry Asian Man. Basically there's nothing I can say about it that he didn't say, or that I haven't already said before. This movie looks bad because it's problematic, implausible, and based on a video game. Just another case of casting being unfair. If we were to argue, as it has been done before, that an actor's race shouldn't factor into casting (which is completely true in many, many cases), we really shouldn't be seeing so many movies with casting like this.

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, August 1, 2009

6:30 AM

Asian Appropriation Alert: Prince of Persia

I recently stumbled upon this on Kotaku:

I don't know where to begin saying what's wrong with this. First of all, it's a movie based on a video game. The movies of Final Fantasy, Tomb Raider, and Resident Evil have all shown us what happens when you try to make a movie out of a video game. But to make it even worse, we have Jake Gyllenhaal starring as the eponymous Prince of Persia. We're told in the fucking title that the main character is Middle-Eastern, and we have a white guy playing him.

Now you may be thinking, "this is unrelated to Asian movies, so why are you talking about it here?" Well, first of all, Persia was on the Eurasian continent, in southeast Asia, so I'm not entirely off, geographically speaking. And even if I was, I said in my last post on the subject that despite the title, I'll be talking about incidents involving other races as well. I've just named this series "Asian Appropriation Alert" because most of the examples I see today involve Asian characters, and because it has a nice ring to it. Anyway:

I was criticized on Racialicious for going too far with my argument about the movie based on Hachiko. But I think this is an even more extreme example. With Hachiko, the filmmakers were taking a Japanese story and putting it in an entirely different location. You could argue that there was an artistic reason for this. I think other movies have done the same thing for artistic reasons, although in the case of the Hachiko I don't really see art playing a part. The Prince of Persia movie is an entirely different story, and anyone can tell that just from its title. The movie is called Prince of PERSIA, and it's set in PERSIA, and it's about said Prince of PERSIA. Is Jake Gyllenhaal Persian? Hell no. This is just another example of a movie where a character's race is specifically stated, in the fucking title of the movie, and that character is played by a white person. Even if you think I'm being to sensitive, or whatever, you still have to admit that this makes the movie NOT MAKE SENSE. Movies like these don't only strike a blow against equality, they strike a blow against plausibility.

Personally, I'd rather watch this movie instead:

Posted by

Jake

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

7:59 AM

Asian Appropriation Alert: Hachiko

So you may remember that I did a post a while back about how in way too many Hollywood movies we can see white actors playing Asian characters, and how it sucks because it's symptomatic of how whiteness is viewed as standard in America. Then I followed it up with a short comment about another movie I heard about in which this happened. And I just found out about yet another one. So I've decided to turn it into a series. I don't know whether this will be a weekly series, a monthly series, or a whatever-ly series, since its frequency really just depends on how many movies like this come out. But we'll see how it goes. To start the series off, I'd like to give a brief chronology of this phenomenon in cinema, and then talk about the latest movie to follow this sad trend.

In the early days of Hollywood cinema, lots of people were racist. Like, really really racist. So racist that the highest grossing silent movie of all time featured the KKK as its heroes. Compared to that movie, most of the racism in Hollywood was more subtle, although it's shockingly offensive by today's standards. In most early movies, Asian characters can be lumped into a few different categories. There are the submissive Asian women, the evil Fu Manchu type characters, and the asian immigrants with horribly mangled "Engrish," just to name a few. And usually these horrible stereotypes were played by white people. Not only did white people keep Asians down by portraying them in negative, generic ways, but also by making sure that they weren't actually able to act in movies. The practice of having white people wear makeup to make them look Asian is known as "yellowface." (I know that the term itself sounds horribly racist, but it's a legitimate term, I swear, and it's actually used by anti-racist people. Just look it up on wikipedia.) This word was derived from the similar word "blackface," which you should probably know the meaning of. The most famous example of yellowface is probably the Charlie Chan series, in which actor Warner Oland played Asian detective Charlie Chan. In fact, Oland actually made an entire career out of pretending to be Asian; he played Fu Manchu in another film series, as well as other Asian characters in other movies. Even when Oland died, the filmmakers didn't decide to cast an Asian actor to replace him. They replaced him with Sidney Toler, who seems like the worst actor ever. Just watch this video (you can even see black stereotypes in it too).

Obviously, anyone who dons racist makeup and speaks in a horrible accent is probably not a good actor, but this guy is just beyond awful.

By the 1970s, yellowface was used much less frequently, and when it was, it was sometimes actually incorporated into the plot, like where a white character would use it as a disguise or something (not that this is OK either, but at least in this case no parts were taken away from Asian people). One of the last movies to feature yellowface prominently was the first Bond movie, Dr. No, in which Joseph Wiseman played the eponymous Asian villain. But after this, yellowface started to fade away. There were only 5 movies featuring yellowface in the 80s, and only one in the 90s.

And now it's 2009. Obama's president, racism is over, and everyone's happy and able to do anything they want, right? Wrong. While yellowface isn't commonplace anymore, it has been replaced by something else. Right now it's unacceptable for an Asian character to be played by a white person in makeup. But it's totally cool for an Asian character to be played by a white person who isn't wearing makeup. Especially if the character's name is changed so that the character isn't even Asian anymore. In this way, stereotypes aren't perpetuated nearly as much, but parts are still taken away from Asian actors. If you want to read more about this, just read my post about it. Or if you want to just know which movies I cited as examples, here they are: the live action versions of Akira, Dragonball, Avatar, and Cowboy Bebop, as well as the movie 21.

On top of this new form of appropriation, yellowface is sadly making a return. If you look on the wikipedia list of movies that feature Yellowface, you'll see that there was one in 1997, the only one in the 90s, and that the next ones after that are four from 2007: Norbit, Grindhouse, Balls of Fury, and I Now Pronounce You Chuck And Larry. To be fair, all of these appearances of yellowface are incredibly small, but it's still alarming that yellowface is actually returning so quickly all of a sudden. It being the "post-racial" 2000s, where race just isn't an issue anymore (please note internet sarcasm), and considering which movies these were, it's clear that yellowface is making a return in the form of ironic racism and equal opportunity offensiveness. When these movies have yellowface appearances in them, they're meant for shock value, and some people think that they reflect positively on the actors ("Look how far Rob Schneider is willing to go! Look at how he doesn't care about race!" BTW why would anyone praise Rob Schneider?). And if someone else were to call it racist, then they would just be called racist, because they're the ones who are "noticing race" (as if noticing race and being racist are the same thing, and as if the one who puts on make-up in order to look Asian truly doesn't notice race). Anyway, this is kind of a tangent, but I'm thinking of doing a more in-depth post on equal opportunity offensiveness in the near future.

Anyway, here's the latest example, which I saw an ad for two days ago, in Japan of all places.

This movie is based on a true story that happened in Japan. A Japanese professor had a dog named Hachiko that would wait for him every day at the train station. One day, the professor died before returning, and the dog continued to wait for him every day. Hachiko is so famous in Japan that there is a statue of him in Tokyo in front of the station where he waited. There is even an annual festival to honor Hachiko. Hachiko is obviously an important symbol in Japan. And his story is being turned into an American movie that takes the story completely out of context. While there is Japanese writing on this poster, that's because this is a poster for the Japanese release of it, not because the movie mentions Japan at all. It's set in Rhode Island, and stars Richard Gere, Joan Allen, and Jason Alexander. All white actors. In Japan, the story of Hachiko is one about loyalty, and it's a story that has great cultural significance. From the looks of this poster, the movie will be much more sappy, and from everything I've heard about it, all of the its cultural significance will be stripped away. This is a Japanese story. It's being sold in America as an American one. And there aren't even any Asian lead actors. This is based on a story about Asian people, and none are present. The only remotely Japanese character is the dog, who happens to be an Akita, and has a Japanese name. Everything else is changed, and Asian countries, Asian cultures, and Asian people are still being ignored. Hollywood isn't progressing in this regard. In fact, lately it's been getting worse.

So now, whenever I see an ad for a movie like this, I'm gonna do a post about it, because it's a trend that's really in full force in Hollywood right now. Also, there are a few older movies that I'd like to do posts about in this series (Memoirs of a Geisha, The Departed, and some others), and also I know that this happens with non-Asian characters as well, so maybe I'll write about those if I don't see many more ads like this. And I would like to say that while there are many movies in which the character's races don't matter, there are also many others where having someone of a different race play a character just leads to the story making less sense. And the fact is that if a character's race truly doesn't matter in any movie, then there should be way more diversity in casting. All white casts still show a bias in Hollywood, especially when the characters were originally of different races. I can't think of any examples of this happening the other way around, where white characters are played by people of other races. If you can think of any, please let me know, but until then I'll stick to criticizing this trend in cinema.

Posted by

Jake

Thursday, June 4, 2009

9:25 AM

More Geeky/Random Web Clippings

I have a few (actually a lot) of my own to add:

10 Video Games That Should Be Viewed As Modern Art

A History of Robot Vocals in Music

The Worst Song in the World

Weird Japanese Commercials Starring Oscar Nominees

One of the Weirdest, Most Fucked Up Extensions of Colonialism I've Ever Seen

A Synth on the Nintendo DS

Barack Obama Cursing

Did George W. Bush's Grandfather Steal Geronimo's Skull?

The Importance of Being Bilingual

One Reason I'm Nervous About Going to Japan

Posted by

Jake

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

7:50 PM

Labels:

comedy,

internet,

language,

links,

music,

obama,

pop culture,

race,

video games,

web clippings

Why, Leo, Why?

It started out with just one movie. Then two, then three, now four, and probably more very soon, in what one of my professors described as "a frickin epidemic." All over the country, perfectly good (well, that might be a bit of a stretch) anime shows and movies are being turned into live- action movies, which on its own creates the potential for true mediocrity. But what makes it even worse is that all of them star white casts.

The first news I heard of this had to do with the upcoming movie of "Avatar: The Last Airbender," which isn't really an anime but is heavily influenced by the style and has to do with Asian culture. This wasn't actually the first movie to be based on an anime and star white people: Speed Racer did it over the summer. But this was the first time that I thought about how problematic it was to have a white person star in a movie based on a cartoon that has Asian characters in it, and soon I started noticing a trend. A few weeks later, my friend told me "Dude, they're making a movie of Dragonball and it's going to have Chow Yun Fat in it." My immediate response was "Sweet! That's so awesome that he's going to play Goku!", but then my friend told me "No, he's playing someone else, the teenager from War of the Worlds is going to play Goku," to which I probably said "What the fuck?" But it didn't stop there: soon I was reading in Giant Robot magazine about how Leonardo DiCaprio was going to produce a live-action movie of Akira. My initial response was "Cool, he's really talented, I bet he'll find some good Japanese actors for it. I mean, it IS set in Tokyo." But then I read about how it was basically going to be a vanity piece for him which he, along with Joseph Gordon Levitt, another great actor, but one who doesn't really fit the character description, is going to star in. The day after I learned about this and spent a good deal of time wondering why this bizarre trend was occurring, my friend told me that Keanu Reeves was going to star in the movie of Cowboy Bebop. When I heard this, it was like a pain in my heart. Cowboy Bebop was one of my favorite anime shows back in the day, and I wish it was being shown more respect.

What, you may ask, is so problematic about this? Well, the answer is pretty straightforward. Anime shows and movies are usually made in Japan by Japanese people, and therefore they are usually about Japanese people as well. People always say that anime characters look white, but this is really just a matter of perception. In America, whiteness is viewed as standard (I could go into why this in itself is problematic, but I'll save that for another time), so generic looking characters are assumed to be white, and non-white characters are usually given distinctive physical features. In Japan, as would be expected, being Asian is viewed as standard, so generic looking characters are assumed to be Asian. Because of this, when white people see a generic looking character in anime they assume that they are white. This is of course a broad generalization, but it has been written about before and makes a lot of sense.

Anyway, it logically follows that if an anime is about Japanese people, and a live action version of it is going to be made, then Japanese people should be cast for it. Well, apparently other people don't think so because of this issue of perception. When white Americans make live action versions of anime shows or movies, they see "standard" characters, assume that these characters are white, and then cast white people for the roles. Again, the fact that white people are all of a sudden all jumping on board to make (presumably) Americanized versions of Japanese movies and shows could in itself be viewed as problematic, but it wouldn't be viewed in this way nearly as much if Japanese people, or at least Asian people, were cast in the leading roles. The reason why this whole situation is fucked up is because it shows how easy it is for white actors to get movie roles compared to Asian actors (and non-white actors in general). Even in movies that are based on Japanese media, set in Japan, and about Japanese people, white people are the stars. This is just beyond ludicrous. I mean, now that Leonardo DiCaprio is going to star in Akira, what's next? Is Tom Cruise going to star in a samurai movie? Is a heavily made-up white guy going to play an Asian Bond villain? Is Ben Kingsley going to play Gandhi in a biopic? Come on, let's not be ridiculous.

Anyway, it's pretty easy to see that the film industry is prejudiced to a startling degree in favor of white people. I wouldn't say this if I was only talking about one movie (even though it's true), but this is more: it's an entire trend in film that's in full force right now. When white people play Asian characters all the time but the reverse is not true nearly as often (to my knowledge, at least), you know that there's absurd amounts of bias within the industry. But even if you don't care about race and you think anyone should be able to play anyone (which even if you think is good is not what the industry is actually like), you have to admit that this whitewashing of Asian media is leading to shittier movies. For one thing, they're just not plausible if you stop to think about them. Avatar and Dragonball are definitely bad in this regard, but Akira is by far the worst. I don't know about you, but I don't think there are very many people with blond hair and blue eyes named Tetsuo who live in Tokyo.

Now, the Cowboy Bebop movie could be considered an exception to this implausibility. For one thing, Keanu Reeves is half Asian. For another thing, the show takes place in outer space, not Japan, and Reeves's character, whose name is the very American/European sounding Spike Spiegle, was born on Mars, which could mean anything in terms of his race. But even with the plausibility significantly increased, Keanu Reeves is a terrible actor. It's bad enough that he just destroyed one of my favorite 50s sci-fi movies, but now he has to ruin one of my favorite Anime shows. In the original show, Spike was an incredibly compelling character, but Keanu Reeves has never been compelling in his life (well, except for when he played Ted Theodore Logan). The reason why I say that Cowboy Bebop deserves more respect is not because of any issues of representation; I simply think it should star someone who is talented enough to play Spike.

This isn't the only case where a sub-par (well, in this case half) white actor has beaten (presumably) talented Asian actors for a role. Jim Sturgess, the British guy from Across the Universe, was supposedly chosen to play an Asian person in the movie 21 because "producers simply sought the best actor for the job, regardless of race. Ultimately, this meant passing over many Asian American talents in favor of London born Jim Sturgess, who required a dialect coach to speak with an American accent." Seriously? A white British guy who needed a dialect coach to even sound like the character was chosen to play an Asian American character, even though tons of people who both looked and sounded like the character auditioned for the role? Even if Sturgess was the best actor overall who auditioned (which I doubt was the case), was he really "the best actor for the job" if he didn't fit the character description at all and required special treatment in order to play the part? I don't buy it, and if the producers of the Dragonball or Cowboy Bebop movies tried to use this argument on me I wouldn't buy it either. Keanu Reeves? That whiny dude from War of the Worlds (no, not Tom Cruise, the other one)? They were really the best actors you could find? I doubt it. The only case where I might buy this argument is with Akira. I think that Leonardo DiCaprio and Joseph Gordon Levitt are both insanely talented actors, and that in many cases they would be better than anyone else auditioning for a part. But in the case of Akira, we run into the issues of representation and plausibility again. I'm sorry, but it's just wrong to have DiCaprio and Levitt be the stars of a movie set in Tokyo, unless it's a remake of Lost in Translation or something (which I probably wouldn't want to watch anyway). Maybe they'll set the movie in a different city to make it more believable, but if that were the case then so much would be lost. The movie would be taken completely out of context and lose lots of meaning, which happens a lot when cultural artifacts are appropriated.

And again, the real problem in this case that arises from cultural appropriation is that it is obviously so much easier for white actors to get movie parts than Asian actors. If Leonardo DiCaprio and Joseph Gordon Levitt were chosen over Asian actors to play characters whose race was not already specified then that wouldn't really be a problem; I would totally believe that they were the best actors for the job and I would probably be excited for the movie and want to go see it (I can't say the same thing for Keanu though). But I'm not excited for the remake of Akira, even though I love the original movie and both actors who will star in it. I think it's absurd and unfair that DiCaprio and Levitt have been cast for the movie, which will be much less authentic and much more removed from the original as a result.

Posted by

Jake

Friday, January 16, 2009

7:45 PM

Wakka's Time Now

Let me start off by saying that the Final Fantasy video game series is absolutely incredible. (Yes, in case you had any lingering doubts, I'm a complete nerd.) Not only has nearly every game in the series been thoroughly enjoyable, but some of them have even revolutionized the genre of role-playing games. The first installment in the series, simply titled "Final Fantasy," provided the template and set the standard for practically every Japanese RPG that came after. And later, with Final Fantasy VI and Final Fantasy VII, developers Squaresoft experimented with the template they had created years earlier and raised the bar for RPG quality even further. With Final Fantasy VI, the developers changed the familiar medieval fantasy environment into a more industrial steam-punk environment and fully realized the storytelling capabilities of video games by creating a massive cast of emotionally complex characters. Then, not content with revolutionizing the genre they had essentially created already only one time, they decided to revolutionize it again with FFVII, changing the newly-established steam-punk environment into a high-tech sci-fi environment, and rendering the game in (at the time) impressive 3D graphics. Because the visuals of FFVII are primitive by today's standards, it is hard to grasp how truly incredible they were when it was first released.

FFVII also marked a step forward for Final Fantasy in a way that is less commonly recognized: it contained the first black playable character.

Up until that point, every FF character had been white or, in a few cases, racially ambiguous. Part of this might have been due to the fact that every FF game before FFVII had been set in a European-themed setting, but this is kind of a copout, especially considering the sheer amount of unique characters in FFVI. I'm sure many people were excited when they found out that FFVII would finally include a black person. Likewise, I'm also sure that these same people were very disappointed when they found out that said black person was Barret, a loud, foul-mouthed, stereotypical cross between Mr. T and Jules Winnfield.

Up until that point, every FF character had been white or, in a few cases, racially ambiguous. Part of this might have been due to the fact that every FF game before FFVII had been set in a European-themed setting, but this is kind of a copout, especially considering the sheer amount of unique characters in FFVI. I'm sure many people were excited when they found out that FFVII would finally include a black person. Likewise, I'm also sure that these same people were very disappointed when they found out that said black person was Barret, a loud, foul-mouthed, stereotypical cross between Mr. T and Jules Winnfield.

I pity the fool who thinks this is fair representation.

Now, I haven't actually played FFVII, so I wouldn't be completely justified in going on a long-winded rant about Barret. I would, however, be more than justified in going on a long-winded rant about Wakka, a character in Final Fantasy X, which I'm currently playing.

Wakka is to Latinos what Barret is to black people; he's the first one of his kind in a Final Fantasy game, and he's also a complete stereotype. Now, Wakka is never explicitly labeled as Latino (largely because the planet Earth doesn't exist in the FF universe, and therefore neither do Central or South America), but he doesn't have to be -- his voice tells you everything you need to know. Just watch this video for an example of what some of Wakka's dialogue sounds like. It's from very early in the game, so there aren't any spoilers or anything.

Now, video games generally aren't known for quality voice acting, but Wakka brings this standard to an entirely new low; I mean, I'm pretty sure whoever did his voice was told to do his best impression of Carlos Mencia doing his best impression of Strong Bad. His voice isn't the only stereotypical aspect of his portrayal though: he's tough but not very bright, he's deeply religious, and if you're still not sure what race he's supposed to be, he even has darker skin than everyone else in FFX (except for maybe Kimahri). And if you think that I'm just over-analyzing things and looking for stereotypes where none actually exist, just take into account the fact that everyone else I know who's played FFX has the same opinions about Wakka that I do. Plus, my descriptions and that one cutscene really don't do justice to Wakka's portrayal. If you want to actually see what I'm talking about you should really play FFX for yourself and make your own observations. Even if you've already played FFX and disagree with me, play parts of it again with these thoughts in mind and you'll see that at the very least, Wakka's darker skin and accent serve to make him ambiguously "ethnic" (I've also heard people describe Wakka as an "islander" stereotype), and his simplistic worldview serves to make him ambiguously "different." Maybe Squaresoft created all this ambiguity to avoid making the same mistake they did with Barret. After all, I don't think anyone has written anything else about Wakka in regards to his portrayal the same way that people have about Barret.

Now, if you're expecting me to continue on this long-winded rant, I'm sorry to disappoint you, but I actually want to write about why I forgive Squaresoft for their portrayal of Wakka. Yes, that's right, I forgive them. I do so with reluctance, but also for several good reasons. One is that Wakka's portrayal is remarkably consistent with Cedric Clark's theory of the four stages of media representation. Clark has argued that oppressed groups tend to go through four different stages of representation in popular culture. In the first stage, nonrecognition, members of said group are never seen anywhere in popular culture; according to the producers of mass media, people from this group simply don't exist (for example, the absence of black people in FF I-VI). In the second stage, ridicule, people from this group are shown, but they are ridiculously stereotyped, often for comedic effect (Barret definitely existed in this stage). In the third stage, regulation, members of this group are portrayed as people who protect the social order, such as police officers or soldiers (it could be argued that Barret simultaneously existed in this stage as well; after all, he was a soldier in FFVII, and was one of its heroes). And in the fourth and final stage, respect, members of this group are, well, respected, being shown frequently and in a variety of ways, both positive and negative (I don't think any group has reached this stage yet in Final Fantasy games). I would argue that Wakka occupies a similar space to Barret in relation to these four stages; while he occupies ridicule, being stereotyped as well as the butt of jokes at times, he also occupies regulation, being one of the heroes of FFX - after all, his job title in the game is "guardian." So while Wakka's portrayal is not the best it could be, it is still, according to Clark's theory, progress. That said, Squaresoft still has a long way to go in this process, and I won't continue to forgive them unless I see some totally non-stereotypical dark-skinned people in future FF games.

The second reason I forgive them is the context in which Wakka was originally portrayed was undoubtedly different in Japan. While Japan does have a substantial Latin American immigrant population, the stereotypes that I observed in Wakka, such as being "tough" and religious, are stereotypes that I know from American media. The argument that racism exists in a different context in Japan has been brought up before in debates about FFVII, as well as other games such as Loco Roco. Loco Roco is a particularly interesting example because its stereotypes are drawn from blackface caricatures, some of the most racist products of American popular culture, but also ones that have frequently been appropriated in Japanese popular culture. There has been an interesting exchange between American and Japanese popular culture that has been occurring for decades, and it has gone something like this:

Step 1. America creates racist caricatures of black people and exports them to other countries, such as Japan.

Step 2. These images surface in Japanese popular culture, where, devoid of cultural and historical context, and in a country that doesn't have a large black population, people don't really get offended by characters like Mr. Popo.

Step 3. These images get exported back to America, where by now everyone considers blackface racist, and people become offended.

Now, people often have a hard time distinguishing which images in Japanese popular culture are derived from blackface caricatures, so the outcry in America is usually small, but sometimes it results in images being changed in American versions of anime and video games, such as with the pokemon Jynx. Other characters, such as Barret, are not derived from the same caricatures, but they do show the same process, where stereotypical images of black people from American popular culture are reproduced in Japan and then given back to an American audience that takes issue with some of these images. Because Wakka's portrayal is more ambiguous, and with a different ethnic group, I don't know if this argument applies in the same way. Wakka is obviously reminiscent of stereotypical images of Latinos from American popular culture, but he could also be a product of prejudices against the Latin American population in Japan. But within the fact that I don't know as much about who Wakka's supposed to represent or what racism is like in Japan lies another one of my arguments: I don't even know if Wakka was stereotypical in the original Japanese version.

I would argue that the most stereotypical aspect of Wakka's portrayal is his voice; if Wakka was just some tough, dark-skinned religious dude who talked the same as everyone else in FFX, I don't know if I would immediately jump to the conclusion that he was a stereotype. This aspect of his portrayal is completely the fault of the American localization staff; when translating the game, the American staff had to hire voice actors to do Wakka's voice, so Wakka definitely sounds different in the original Japanese game. I looked up who did Wakka's voice in the American version, and it turns out it was John DiMaggio, a white guy who did the voice for Bender in Futurama. Needless to say, he obviously put on some kind of accent to do Wakka's voice. Because of this, while I forgive Squaresoft for Wakka, I can't forgive the American localization staff. If Wakka was originally based on stereotypical media images, then the localization staff should have known what effects these images would have when being shown again in America. And if Wakka was portrayed differently in the original version and was turned into a stereotype for the American release, well then shame on the localization staff.