A while ago, one of my friends burned for me,

among many other albums, a compilation of UK hip hop. Being a fan of

both hip hop and music from the UK, needless to say I was excited to

listen to it. When I did, I was… well, not disappointed, but very very

surprised. The music wasn't at all what I expected. It didn't sound

like hip hop to me. It sounded like… dancehall.

This little

incident of mine is just one example of the ways in which hip hop and

dancehall are connected not only to each other, but also to many other

types of music, as was illustrated fabulously in Wayne Marshall's piece

on reggaeton. It is also an example of how perceptions of music are

formed by people who are outsiders to certain genres. Since I'm in no

way a part of any hip hop scene, especially UK hip hop, this experience

was eye-opening for me, since, despite how insignificant it may seem,

it really challenged my perceptions of music and genre.

As

Marshall illustrated, reggaeton came into being as a result of

influences from hip hop, reggae, and dancehall, among many other

musical forms. The example of reggaeton is just one illustration of how

hip hop and dancehall are related to each other. The exact relationship

between these two forms isn't a completely clear one, and theories

about this relationship have been controversial at times. One of the

most commonly posed theories is that New York hip hop was essentially

an American variation of the Jamaican dancehall tradition, where DJs

would spin versions of records that would be toasted over. The

similarities in form between dancehall and New York hip hop are

noticeable, and it is easy to see why this theory has been raised,

especially since DJ Kool Herc, one of the pioneers of hip hop, was

originally from Jamaica. However, Herc himself has denied the "hip hop

comes from toasting" theory, saying "Jamaican toasting? Naw, naw. No

connection there." Obviously, hip hop and dancehall have a complicated

relationship with each other.

Before I go further, I'll link a couple songs from this compilation.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rXiM3whh15I

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdTCtYuDpgc

As

one MC descibes the music of the compilation: "This is a UK thing, it's

hip hop and it's reggae and we do reggae - and those Americans don't

know about that." While you might think it would be my gut reaction to

get defensive about a statement like this, that MC is totally right.

I'm American, and I didn't understand that UK thing when I listened to

it. While I was aware of the connections between reggae, dancehall, and

hip hop when I listened to this compilation, I was still baffled by the

idea that songs so easily classifiable as dancehall or reggae, with

their distinct rhythms, could also be considered hip hop. It was a

direct acknowledgement of the connections between these forms, and it

took me by surprise.

Part of the reason these songs didn't

sound like what I expect hip hop to sound like is that they don't have

rhythms I associate with hip hop. Marshall illustrated very well how

certain rhythms are associated with certain genres, but that there is

lots of hybridity between those genres, and some artists consider

reggaeton, for example, to be a type of hip hop, even though it has its

own rhythm. So even though these songs have rhythms associated with

dancehall and reggae respectively, they are still lumped in with hip

hop, since often times the only thing separating these genres are the

rhythms. But that's not everything. Language also plays a very

important role.

This raises a somewhat harsh, but important

question: if all of these forms are interconnected, who am I to

determine what category a piece of music falls into? How does my

perspective as an American influence the way I hear music? And how does

language play a role in this?

This, I think, is where the vocals

come into play. I'm gonna throw out this theory I have for all of you

to read. It's not one that I stand by 100%, since I'm still kind of

working it out in my head, and some of it is just speculation, but I'd

like to see what you think of it. It has to do with how my perspective

as an American informs the way I hear music from other countries.

In

regard to the way I, and Americans in general, hear music from Jamaica

and the UK, vernacular language is one of the most important factors in

how Americans interpret music. As I noted in my last post about white

reggae bands (which caused some controversy when I posted it on my own

blog), in the music of the Police there is a strong association between

Jamaican patois and the sound of reggae that isn't actually there a lot

of the time. I think in general, a lot of American people have a strong

association in their minds between Jamaican patois and

reggae/dancehall. In the minds of many, the lines that separate reggae

and dancehall are very blurry, and while that's in some ways

legitimate, since there's obviously lots of hybridity, it's also

problematic in some ways, and, surprise surprise, there aren't any easy

answers. I mean, on one hand it's problematic to use only use the word

"reggae" in reference to roots reggae ("Be warned that a white person

saying they like “reggae” really means “reggae from 1965-1983." Under

no circumstances should you ever bring a white person to a dancehall

reggae concert, it will frighten them." – Stuff White People Like),

it's also problematic to use "reggae" as a blanket term for all

Jamaican music. I've heard people describe everything from the

Skatalites to Sean Paul as reggae, denying that they were listening to

ska/dancehall and insisting that ska didn't exist until the 90s/Sean

Paul's vocals are in patois, so it's totally reggae. That last point

about Sean Paul is kind of what brings it all back to the UK hip hop

compilation. In the ears of the listener, a lot of times what makes

something "reggae" or "dancehall" is the vocals, since people associate

Jamaican patois with music that they clearly identify as Jamaican.

Sting did this in the Police. The person who insisted that Sean Paul

plays reggae in the same way Bob Marley does wasn't familiar with the

term dancehall, so rather than describing Sean Paul as hip hop or rap,

he used the word reggae, since it referred to Jamaican music for him.

Even though the song he was listening to didn't have a reggae rhythm,

he heard Jamaican patois and classified the music as reggae. When I

listened to the UK hip hop compilation, I knew about other kinds of

Jamaican music, so when I heard the vocal presence of Jamaican

immigrants, I immediately thought dancehall, since I knew it didn't

have a reggae rhythm, but I still had the initial reaction of thinking

of it in terms of Jamaican music, because of what I heard in the

vocals. The fact that it was described as UK hip hop, but that I

labeled it differently, shows not only that hip hop, dancehall, and

reggae are related in many complicated ways, but also that listeners

have strong preconceptions about what music "should" sound like, and

that someone from America is likely to perceive music in a very

different way than someone from the UK.

Showing posts with label commentary. Show all posts

Showing posts with label commentary. Show all posts

This Is... Reggae? A Long-Winded Analysis of UK Hip Hop

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, December 12, 2009

2:56 PM

What to Make of White Reggae Bands

I've brought up stories and commentary before about white people who consume reggae, a historically black musical genre (I totally fall under the category of white people who consume reggae). Now I'd like to complicate things a little by talking about white producers, rather than consumers, of reggae. In order to do this, I'd like to examine three (primarily) white bands that have played reggae, or at least reggae-influenced music: The Police, UB40, and The Aggrolites.

First, lets look at the Police. While I'll acknowledge that Stuart Copeland is an awesome drummer, Sting's fake Jamaican accent has always annoyed the shit out of me. Let's listen to an example:

While The Police were never really a reggae band by definition, the song "Walking on the Moon" is one of the best examples of the massive reggae-influence on their music, which can also be heard in Sting's vocals. For their first few albums, Sting put on a ridiculous fake Jamaican-style accent (he never really got it right), presumably to try and imitate the Jamaican Patois heard in many reggae songs. The thing that's always amazed me though is that Sting really really overcompensated. Let's listen to a song by Jimmy Cliff to compare:

Notice anything different? I've been in linguistics classes where we've examined Jamaican Patois, and one thing we've noticed is that Jimmy Cliff doesn't really use it in his songs. The same goes for a lot of other reggae singers. In the music of the Police, however, Sting makes a huge effort to put on a Jamaican accent. The other thing to note is that Sting phased out the fake accent later in his career, but by this point the Police were playing a lot of other stuff besides reggae-influenced-pop. Basically the point I'm trying to make is that in the reggae music of the Police, Sting used a fake Jamaican accent as a signifier of reggae, even though he really didn't need to, since Jimmy Cliff didn't, and he's one of the best reggae singers of all time.

So, to reference a question raised by scholar Terry Boyd in relation to hip hop, is the music of the Police an imitation of reggae, or is it influenced by reggae? Well, the answer is both. They're not mutually exclusive. I kind of think that to an extent one implies the other, and you'll noticed that I've already used both words in describing The Police. The point, however, is that, to an extent at least, the music of the Police WAS an imitation, since Sting pretty blatantly imitated Jamaican English, which he at least saw as a major signifier of reggae.

On to the next example: UB40. The two things that really really separates them from The Police are that

1. They were obviously a reggae band, and

2. They were an even more blatant imitation

I'm not even gonna try and defend their music, since it was almost 100% imitation, rather than influence. Seriously, they became famous just by covering reggae songs that were already hits in Jamaica. The album that made them famous, Labour of Love, is all covers. I've listened to every song on that album, and I've listened to the original versions of every song on that album, and in every case the original is better. Actually that's just a matter of opinion for me, but my point about UB40 is that they fall under the category of imitation rather than influence, since they made massive amounts of money by literally imitating reggae songs that had already been played by less successful people. And their lead singer, who was also white, also sang in a fake Jamaican accent. I would go so far as to call UB40 the Elvis of reggae.

Anyway, let's move on to my last example: The Aggrolites. They're even more noticeably different from the other two examples, because:

1. They're American

2. They're not as popular

3. They play a very different style of reggae

4. They don't put on ridiculous accents

The last point is reason enough to believe that the Aggrolites fall less under imitation and more under influence. But the other thing that makes the Aggrolites stand out for me is that, unlike The Police and UB40, who use fake Jamaican accents as a reggae signifier, The Aggrolites use something very different as a signifier: the skinhead image. Just to provide some background, the skinhead subculture originally emerged in England in the 1960s and was in no way affiliated with Neo-Nazis. While the original skinheads did exhibit racism towards Indian and Pakistani immigrants, they showed solidarity towards Jamaican immigrants, and were huge fans of reggae and ska. As a result, some reggae bands, most notably Syramip, began targeting their music towards skinheads, most obviously in the song "Skinhead Moonstomp."

Now listen to this song by the Aggrolites and compare it to the Jimmy Cliff song and the Syramip song:

This one is obviously more influenced by Syramip than Jimmy Cliff; the tempo is almost exactly the same, the production is just as minimal, and the vocals are shouted and chanted rather than sung. I've also seen The Aggrolites live, and they performed Skinhead Moonstomp. Basically, The Aggrolites choose to use the skinhead subculture as a reference point for the reggae that they play. This choice is still problematic, no question. But they're not pretending to be Jamaican. There are two factors at play in this. For one, by referencing skinheads the Aggrolites show a familiarity with the history of reggae. The Police and UB40 just put on fake accents as an obvious way of saying "This is reggae," but the Aggrolites choose instead to reference an aspect of reggae that people might not be as familiar with, showing their familiarity with the music. It should also be noted that while The Police and UB40 played music that had all the surface elements of reggae as a way to make money, the Aggrolites have played a different type of reggae and not been as successful. The second factor at play is that by referencing the skinhead subculture, it could be argued that The Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as outsiders of reggae. While not all of The Aggrolites are white, not all skinheads were white either, and by referencing skinheads rather than trying to sound Jamaican, the Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as consumers of reggae and not pretending to be the original producers of it. Both strategies are ways to claim authenticity, but the strategy the Aggrolites employ is one that acknowledges their outsider status.

So to return to that question again, do the Aggrolites imitate reggae, or are they influenced by it? Again, the answer is both. The two aren't mutually exclusive, and I think it's almost impossible for them to be entirely separate. But since, by referencing skinheads rather than just putting on fake accents, the Aggrolites have engaged with the history of reggae and also acknowledged their status as outsiders in reggae, I'd say they fall more under the category of influence.

First, lets look at the Police. While I'll acknowledge that Stuart Copeland is an awesome drummer, Sting's fake Jamaican accent has always annoyed the shit out of me. Let's listen to an example:

While The Police were never really a reggae band by definition, the song "Walking on the Moon" is one of the best examples of the massive reggae-influence on their music, which can also be heard in Sting's vocals. For their first few albums, Sting put on a ridiculous fake Jamaican-style accent (he never really got it right), presumably to try and imitate the Jamaican Patois heard in many reggae songs. The thing that's always amazed me though is that Sting really really overcompensated. Let's listen to a song by Jimmy Cliff to compare:

Notice anything different? I've been in linguistics classes where we've examined Jamaican Patois, and one thing we've noticed is that Jimmy Cliff doesn't really use it in his songs. The same goes for a lot of other reggae singers. In the music of the Police, however, Sting makes a huge effort to put on a Jamaican accent. The other thing to note is that Sting phased out the fake accent later in his career, but by this point the Police were playing a lot of other stuff besides reggae-influenced-pop. Basically the point I'm trying to make is that in the reggae music of the Police, Sting used a fake Jamaican accent as a signifier of reggae, even though he really didn't need to, since Jimmy Cliff didn't, and he's one of the best reggae singers of all time.

So, to reference a question raised by scholar Terry Boyd in relation to hip hop, is the music of the Police an imitation of reggae, or is it influenced by reggae? Well, the answer is both. They're not mutually exclusive. I kind of think that to an extent one implies the other, and you'll noticed that I've already used both words in describing The Police. The point, however, is that, to an extent at least, the music of the Police WAS an imitation, since Sting pretty blatantly imitated Jamaican English, which he at least saw as a major signifier of reggae.

On to the next example: UB40. The two things that really really separates them from The Police are that

1. They were obviously a reggae band, and

2. They were an even more blatant imitation

I'm not even gonna try and defend their music, since it was almost 100% imitation, rather than influence. Seriously, they became famous just by covering reggae songs that were already hits in Jamaica. The album that made them famous, Labour of Love, is all covers. I've listened to every song on that album, and I've listened to the original versions of every song on that album, and in every case the original is better. Actually that's just a matter of opinion for me, but my point about UB40 is that they fall under the category of imitation rather than influence, since they made massive amounts of money by literally imitating reggae songs that had already been played by less successful people. And their lead singer, who was also white, also sang in a fake Jamaican accent. I would go so far as to call UB40 the Elvis of reggae.

Anyway, let's move on to my last example: The Aggrolites. They're even more noticeably different from the other two examples, because:

1. They're American

2. They're not as popular

3. They play a very different style of reggae

4. They don't put on ridiculous accents

The last point is reason enough to believe that the Aggrolites fall less under imitation and more under influence. But the other thing that makes the Aggrolites stand out for me is that, unlike The Police and UB40, who use fake Jamaican accents as a reggae signifier, The Aggrolites use something very different as a signifier: the skinhead image. Just to provide some background, the skinhead subculture originally emerged in England in the 1960s and was in no way affiliated with Neo-Nazis. While the original skinheads did exhibit racism towards Indian and Pakistani immigrants, they showed solidarity towards Jamaican immigrants, and were huge fans of reggae and ska. As a result, some reggae bands, most notably Syramip, began targeting their music towards skinheads, most obviously in the song "Skinhead Moonstomp."

Now listen to this song by the Aggrolites and compare it to the Jimmy Cliff song and the Syramip song:

This one is obviously more influenced by Syramip than Jimmy Cliff; the tempo is almost exactly the same, the production is just as minimal, and the vocals are shouted and chanted rather than sung. I've also seen The Aggrolites live, and they performed Skinhead Moonstomp. Basically, The Aggrolites choose to use the skinhead subculture as a reference point for the reggae that they play. This choice is still problematic, no question. But they're not pretending to be Jamaican. There are two factors at play in this. For one, by referencing skinheads the Aggrolites show a familiarity with the history of reggae. The Police and UB40 just put on fake accents as an obvious way of saying "This is reggae," but the Aggrolites choose instead to reference an aspect of reggae that people might not be as familiar with, showing their familiarity with the music. It should also be noted that while The Police and UB40 played music that had all the surface elements of reggae as a way to make money, the Aggrolites have played a different type of reggae and not been as successful. The second factor at play is that by referencing the skinhead subculture, it could be argued that The Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as outsiders of reggae. While not all of The Aggrolites are white, not all skinheads were white either, and by referencing skinheads rather than trying to sound Jamaican, the Aggrolites are acknowledging their status as consumers of reggae and not pretending to be the original producers of it. Both strategies are ways to claim authenticity, but the strategy the Aggrolites employ is one that acknowledges their outsider status.

So to return to that question again, do the Aggrolites imitate reggae, or are they influenced by it? Again, the answer is both. The two aren't mutually exclusive, and I think it's almost impossible for them to be entirely separate. But since, by referencing skinheads rather than just putting on fake accents, the Aggrolites have engaged with the history of reggae and also acknowledged their status as outsiders in reggae, I'd say they fall more under the category of influence.

Posted by

Jake

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

10:57 PM

Don't Believe The Hype: A Criticism of Criticisms of Rap

"Every generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it." – George Orwell

"Although American rap music has been used as a vehicle for the creation of novel indigenous musical styles (in South Africa), it has come under heavy criticism from the older generation of South African musicians, some of whom have dismissed indigenous rap as hopelessly imitative of the worst excesses of American culture…. South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela complained that 'our children walk with a hip hop walk and they think they are Americans….' Ironically, the jazz music Masekela… pioneered owed an equal debt to American jazz artists as kwaito does to American rap. Furthermore, Black jazz musicians of the 1950s were subject to similar criticisms by the cultural elite." – Zine Magubane, "Globalization and Gangster Rap."

"The Arabic hip hop genre has faced strong resistance from various cultural forces. Abbas, who traces the development of this genre across the Arab world, argues that this resistance was not necessarily the result of musical evaluation, but rather a natural reaction to anything that sounds western as well as the response of people who feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." – Usama Kahf, "Arabic Hip Hop"

"Those interested in black music and black politics should check out studies on the racial uplift ideology literature of the late 19th Century through 1950s, which reveals, among other things, “New Negro” discomfort with black folk culture (demonstrative church music, blues, jazz, narratives depicting uneducated black folk.). This literature features recurring questions such as “How does popular black art affect the moral training of black children?” and “How will this art make us look to white people?” If you replace all of the “negro”s with “black”s or “African American”s,” you’d swear that these things were written today." – Gordon Gartrelle "The Problem With These Rap Critics Today"

"No question. Rap is the repetition of the minstrel show." – Wynton Marsalis

I know I'm just listing quotes, but that's because the quotes speak for themselves.

If you can't tell already, the aim of this post is to examine some of the most prominent criticisms of rap music. In some ways, these quotes contradict the points that I made in my earlier post about de-politicization. In that post, I discussed how white cultural critics have often criticized black musical forms because of their political aspects. But, as I noted, white critics have never been the only ones to criticize new black (or) political musical forms. As you can see, South African jazz musicians have criticized South African rap, Arabic hip hop has faced criticism in local communities, and Wynton Marsalis, a prominent black jazz musician, has been an incredibly vocal critic of hip hop.

What really amazes me is how almost universal these criticisms are. It seems that no matter what context hip hop is created in, there are always vocal critics of it who attack it using countless different arguments. A lot of these criticisms are valid; lots of feminist thinkers, for example, have rightly noted that a lot of hip hop contains deeply misogynist lyrics. But I think the key phrase in statements like this that makes them valid is "a lot of hip hop." The problem I have with criticisms such those of Marsalis is that they are sweeping generalizations that don't allow any room for exceptions. To label an entire musical form as "the repetition of the minstrel show" is a deeply problematic easy way out. Plus, a lot of these criticisms seem to be representative of an unwillingness to accept new musical forms.

One common thread that seems to lie behind all these criticisms of rap is a desire to hold on to tradition. This ties in to Kahf's quote about how many people "feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." This argument can even be applied to my discussion of musical de-politicization (sorry to reference myself, but I do think it's relevant). The fact that lots of white cultural critics have criticized political black musical forms can easily be read as a desire to hold on to a tradition of power, since these critics feel threatened by hip hop. The critics discussed in the pieces by Magubane and Kahf can also be seen as feeling threatened by other political aspects of hip hop. Globalization is a powerful force, and the United States are one of the most influential countries globally; I observed this first hand while traveling this summer. While hip hop can be used in local communities as a tool of resistance, it still has ties to America, since it is historically an American musical form. This is another way in which people probably feel threatened by hip hop; American media can be seen in lots of different countries, and people who have this media imposed on them may understandably reject American musical forms that can even be used subversively. We can even read Wynton Marsalis's criticism as being a reaction to the threat that Jazz has faced from hip hop, which is a far more popular genre among young people today.

I'd like to discuss Marsalis's statement a little bit more, and why I feel it is so deeply problematic. Lots of people have proposed the "hip hop is minstrelsy" argument before, but some people, such as Jeffrey Ogbar, author of the book Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap, have taken a better approach to it. The problem I have with Marsalis's argument as opposed to Ogbar's is that while Marsalis condemns the entire form of hip hop, Ogbar makes a clear distinction between hip hop he sees as being a reprisal of the minstrel show, and hip hop that he views otherwise. In addition, he also provides historical context on both minstrelsy and hip hop. I don't have a problem with criticizing hip hop, as long as you don't dismiss the entire form, and as long as you back up your ideas without making sweeping claims.

I'll also add that the issue of holding on to tradition vs. accepting globalized music is a really complicated one, and I'm not trying to make it seem like the people who criticize hip hop in a global setting are wrong, since I really don't know enough about the specific contexts. I'm just pointing out that a lot of criticisms of hip hop come out of the same desire to hold on to tradition.

"Although American rap music has been used as a vehicle for the creation of novel indigenous musical styles (in South Africa), it has come under heavy criticism from the older generation of South African musicians, some of whom have dismissed indigenous rap as hopelessly imitative of the worst excesses of American culture…. South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela complained that 'our children walk with a hip hop walk and they think they are Americans….' Ironically, the jazz music Masekela… pioneered owed an equal debt to American jazz artists as kwaito does to American rap. Furthermore, Black jazz musicians of the 1950s were subject to similar criticisms by the cultural elite." – Zine Magubane, "Globalization and Gangster Rap."

"The Arabic hip hop genre has faced strong resistance from various cultural forces. Abbas, who traces the development of this genre across the Arab world, argues that this resistance was not necessarily the result of musical evaluation, but rather a natural reaction to anything that sounds western as well as the response of people who feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." – Usama Kahf, "Arabic Hip Hop"

"Those interested in black music and black politics should check out studies on the racial uplift ideology literature of the late 19th Century through 1950s, which reveals, among other things, “New Negro” discomfort with black folk culture (demonstrative church music, blues, jazz, narratives depicting uneducated black folk.). This literature features recurring questions such as “How does popular black art affect the moral training of black children?” and “How will this art make us look to white people?” If you replace all of the “negro”s with “black”s or “African American”s,” you’d swear that these things were written today." – Gordon Gartrelle "The Problem With These Rap Critics Today"

"No question. Rap is the repetition of the minstrel show." – Wynton Marsalis

I know I'm just listing quotes, but that's because the quotes speak for themselves.

If you can't tell already, the aim of this post is to examine some of the most prominent criticisms of rap music. In some ways, these quotes contradict the points that I made in my earlier post about de-politicization. In that post, I discussed how white cultural critics have often criticized black musical forms because of their political aspects. But, as I noted, white critics have never been the only ones to criticize new black (or) political musical forms. As you can see, South African jazz musicians have criticized South African rap, Arabic hip hop has faced criticism in local communities, and Wynton Marsalis, a prominent black jazz musician, has been an incredibly vocal critic of hip hop.

What really amazes me is how almost universal these criticisms are. It seems that no matter what context hip hop is created in, there are always vocal critics of it who attack it using countless different arguments. A lot of these criticisms are valid; lots of feminist thinkers, for example, have rightly noted that a lot of hip hop contains deeply misogynist lyrics. But I think the key phrase in statements like this that makes them valid is "a lot of hip hop." The problem I have with criticisms such those of Marsalis is that they are sweeping generalizations that don't allow any room for exceptions. To label an entire musical form as "the repetition of the minstrel show" is a deeply problematic easy way out. Plus, a lot of these criticisms seem to be representative of an unwillingness to accept new musical forms.

One common thread that seems to lie behind all these criticisms of rap is a desire to hold on to tradition. This ties in to Kahf's quote about how many people "feel directly implicated and threatened by hip hop's criticism of their way of life." This argument can even be applied to my discussion of musical de-politicization (sorry to reference myself, but I do think it's relevant). The fact that lots of white cultural critics have criticized political black musical forms can easily be read as a desire to hold on to a tradition of power, since these critics feel threatened by hip hop. The critics discussed in the pieces by Magubane and Kahf can also be seen as feeling threatened by other political aspects of hip hop. Globalization is a powerful force, and the United States are one of the most influential countries globally; I observed this first hand while traveling this summer. While hip hop can be used in local communities as a tool of resistance, it still has ties to America, since it is historically an American musical form. This is another way in which people probably feel threatened by hip hop; American media can be seen in lots of different countries, and people who have this media imposed on them may understandably reject American musical forms that can even be used subversively. We can even read Wynton Marsalis's criticism as being a reaction to the threat that Jazz has faced from hip hop, which is a far more popular genre among young people today.

I'd like to discuss Marsalis's statement a little bit more, and why I feel it is so deeply problematic. Lots of people have proposed the "hip hop is minstrelsy" argument before, but some people, such as Jeffrey Ogbar, author of the book Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap, have taken a better approach to it. The problem I have with Marsalis's argument as opposed to Ogbar's is that while Marsalis condemns the entire form of hip hop, Ogbar makes a clear distinction between hip hop he sees as being a reprisal of the minstrel show, and hip hop that he views otherwise. In addition, he also provides historical context on both minstrelsy and hip hop. I don't have a problem with criticizing hip hop, as long as you don't dismiss the entire form, and as long as you back up your ideas without making sweeping claims.

I'll also add that the issue of holding on to tradition vs. accepting globalized music is a really complicated one, and I'm not trying to make it seem like the people who criticize hip hop in a global setting are wrong, since I really don't know enough about the specific contexts. I'm just pointing out that a lot of criticisms of hip hop come out of the same desire to hold on to tradition.

Posted by

Jake

Sunday, November 8, 2009

5:00 PM

Samurai Spirit: Orientalist Images of Japan in Contemporary Film

In her piece "Black Bodies/Yellow Masks," Deborah Elizabeth Whaley identifies four different Orientalist images that are commonly found in popular culture:

"(1) the sexualized, yet virginal Japanese geisha; (2) the South Asian Indo-chic; (3) the Chinese kung fu warrior; and (4) the use of Asian languages as an iconographic fashion statement detached from specificity of meaning and etymological usage."

While these images are important to recognize in popular culture, I also think that Whaley's list comes dangerously close to equating Japan with femininity and China with masculinity. That's why I want to concentrate on #3 in this post, specifically because "the Chinese kung fu warrior" definitely has a Japanese counterpart: the Samurai.

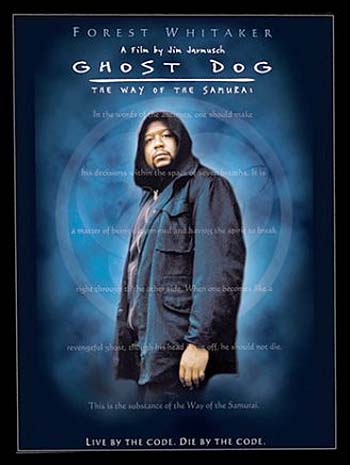

Many people have noted the Orientalist aestheics in the music and imagery of the Wu-Tang Clan. When looking at Whaley's list, it's obvious that the primary image used by the Wu-Tang Clan is #3. This is one reason why I'm using the image of the samurai as a parallel to the "kung fu warrior." The RZA, a member of the Wu-Tang Clan, has composed the score for two movies that I must admit I'm fond of, but that I also must admit show very orientalist images of samurai: Afro Samurai and Ghost Dog. These movies are also good reference points for discussing the same relationships between African American culture and Asian culture that Whaley discussed in her piece.

For this post, I'm going to specifically focus on Ghost Dog, since I've seen it way more times. This movie features Forrest Whitaker (one of a few famous alums of my high school), as a hit man whose entire personal philosophy is based on Hagakure, an 18th century book by Yamamoto Tsunetomo that outlines the code of the samurai. The one thing I will say in the film's defense is that it's based on an actual book, and it would've been way easier for the writers to just make stuff up. Still, the fact that the movie derives almost all of its imagery from this book is problematic. While Whaley is very positive about the use of Asian imagery in African American art, and while the issue is undoubtedly a very complex one, images like these can still be used to produce an essentiallized image of Asia.

It's nothing new for images of samurai to be used in Orientalist ways. Much like the belly dancing discussed in Susaina Maira's piece entitled "Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire," representations of a "samurai code" can be a way to profess an interest in Japan while avoiding discussions of contemporary issues that Japanese people actually face. I spent last semester in Japan, and the only time I was ever involved in a discussion that had anything to do with samurai philosophy was in an art history course, and even then it was only as a small part of one class. But there are still American songs, films, and people that base all their knowledge of Japan on romanticized ideas of the samurai.

I'm reminded of a scene in a movie I just watched called "Kamome Shokudo," which is about three Japanese women who work in a Japanese restaurant in Finland. In the movie, there is a young male Finnish character named Tommi who starts coming to the restaurant because, like many young white males including myself, he has an interest in Japanese culture. In almost every scene that this character is in, he is wearing a shirt that has some representation of Japanese culture, most of which are from contemporary Japanese popular culture (this description might sound eerily familiar for people who know me). Most of the time, the women who work in the restaurant either make some friendly comment about his shirt or don't make a comment about it at all. The only scene in which any of the women have a noticeably different reaction to one of his shirts is when he is wearing one that has the kanji for "samurai spirit" on it. In the beginning of the movie, he wears a shirt with a Japanese cartoon character, and one of the women in the restaurant is able to relate to it. But the woman who comments on the "samurai spirit" shirt is portrayed as being unable to relate to it. I think these scenes are pretty good representations for a number of reasons. Tommi's character is not really portrayed as being Orientalist, and his shirts display a wide range of Japanese cultural artifacts. But the only shirt he wears that is portrayed as being Orientalist is the one that conveys a dated, romanticized notion that doesn't have as much relevance in contemporary Japanese society. This also ties in to #4 on Whaley's list: " the use of Asian languages as an iconographic fashion statement detached from specificity of meaning and etymological usage."

One more thing that I'll comment on is the fact that Chinese and Japanese cultures can be (sometimes inadvertently) portrayed as interchangeable in popular culture. I'm not going to get into this in too much detail, but I do find it interesting that the RZA, a producer who derives much of his aesthetics from Chinese popular culture, did the score for two movies that derive much of their imagery from Japanese culture. This is just one reason why I think that the image of the samurai can be viewed as a counterpart to "the Chinese kung fu warrior."

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, October 31, 2009

5:51 PM

Lego Blur, Lego Bowie, and Legofication

It's time for me to reference Coilhouse again. Specifically, a blog post they did a while back in which they coined a term I fell in love with: "Legofication." According to Coilhouse, legofication refers to the way in which pop songs have started being stacked up against each other in mash-ups, just like legos. It refers to the fact that right now it is common for pop songs to not be viewed as complete wholes, but as pieces that can be put together to make something cooler. I love this idea so much that I'd like to apply it to not just pop music, but pop culture in general.

Originally, I was planning to write a lengthy post about the postmodern aspects of music games like Guitar Hero, DJ Hero, and Rock Band, but then I realized that I didn't have enough time/will-power/intellect to do that, and that it would be way too boring/pretentious. So instead I'm doing a much simpler version of that original idea by specifically focusing on one of the newest music games, Lego Rock Band. I think it's entirely appropriate that a game so heavily constructed around legofication uses legos themselves as part of these pop culture building blocks.

In the Coilhouse piece about legofication, they mention how songs are basically starting to be used as building blocks for mash-ups. I'd like to extend this idea, arguing that in the case of Lego Rock Band pop culture icons are being used as building blocks. While Legos themselves are literally building blocks, the entire lego franchise can definitely be viewed as a pop culture icon as well. This pop culture icon is one building block in the construction of Lego Rock Band; so are the images of Blur, David Bowie, Iggy Pop and Queen. (I have to say I'm impressed with the Lego rendering of Bowie, since they actually gave him two different eye colors.) Bands and singers that are obviously viewed as entire wholes are again being used as building blocks in a larger pop-culture artifact, in a slightly different way from how Coilhouse discusses this idea. These pop-culture entities are rendered using the style of another pop culture entity, and then put inside a third pop culture entity, namely the Rock Band series. It's one thing to make Lego renderings of famous musicians. It's another thing to put images of famous musicians in a video game. And it's another thing to put Legos inside a video game. These have all been done before. But Lego Rock Band is simply taking Legofication to entirely new levels (although this does remind me of the Lego Star Wars and Lego Indiana Jones series).

One question I've been wondering is whether or not anyone actually expects Lego Rock Band to be good. While people might be excited about their favorite musicians appearing together in a video game, too much legofication might not be a good thing. I'm reminded of The Good, The Bad, and The Queen, a supergroup featuring Damon Albarn of Blur, Paul Simonon of the Clash, the guitarist from The Verve (I don't remember his name), and Tony Allen, Fela Kuti's drummer. To top off this list of talent, their album was produced by Dangermouse. And it was really disappointing. Sure the album is fairly good, but considering all the names that went into it, it could've been way better. Now, I don't have high hopes for Lego Rock Band, and I'm sure a lot of people feel the same way as me. The only point that I'm trying to make is that in a lot of cases, Legofication could possibly lead to huge disappointment.

Another question that people have raised about Lego Rock Band is whether or not you'll be able to have Blur play songs by Queen, or whether David Bowie will be able to sing Iggy Pop songs. People have raised this question because there was a lot of controversy over the appearances of Johnny Cash and Kurt Cobain in Guitar Hero 5. In that game, both musicians were able to play songs by other artists, and lots of people had intense reactions to that, since they felt it was disrespectful to the musicians. Now, personally, I think having Kurt Cobain play songs by other artists sounds awesome. But I'm not here to argue about whether or not the inclusion of that feature was a good thing. The point that I do want to make, that comes from the post I was originally planning on writing, is that this feature is one of the most postmodern aspects of these games. One defining element of postmodernism as a movement is pastiche, which throws different cultural artifacts together and either strips them of their meaning or gives them new meaning. (If you think about it, legofication is really just another way of describing pastiche.) Having Johnny Cash playing "Smells Like Teen Spirit" is without a doubt a form of pastiche that dramatically changes the meanings of the cultural artifacts involved. Which is why people got so upset over this.

We can see postmodernism, pastiche, and legofication in DJ Hero as well, a music game that revolves around mash-ups. Again, in this example we essentially have two pastiches put together: the game involves musicians being represented in a video game, and these musicians play songs made up of other songs. In this case, pop songs that have already been legofied are put into another pop culture artifact for further legofication.

Now, I'm not arguing whether or not these games are good. I personally enjoyed Guitar Hero II, and I've also enjoyed playing Rock Band at parties, but I was really disappointed by Guitar Hero III, and I haven't had much interest in these types of games otherwise, although I've read a lot about them on video game and music blogs. But from my experience with these types of games, they are perfect examples of the legofication of popular culture.

Posted by

Jake

Monday, October 26, 2009

12:01 AM

Musical De-Politicization, Nostalgia, and Moral Outrage

I'd like to continue and elaborate on some of the points I made in my piece about canonization.

In Kevin Phinney's piece "Souled American" there was a quote that really caught my attention:

"African Americans are more interested in discovering the Next Big Thing than in riding a fad past its relevance to daily life. Certainly there's no reason for black Americans to romanticize their experience here. This country hasn't provided any good old days for people of color."

Phinney then went on to discuss how white people "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo," and compared "white music" to "an old lamp," referring to its sentimentality and nostalgia. While I do think this is a bit of an over-generalization, I also think there is some truth to it. To understand why, it is important to discuss the ways in which black musical forms have political origins.

Many, many historically black musical forms have been political in some way. Rap is an obvious example, and it's also very easy to hear political sentiment expressed in reggae, soul, and even largely instrumental musical forms like jazz. And in all of the musical forms listed above, race plays a hugely important role in the musical politics. From Louis Armstong's "Black and Blue" to Curtis Mayfield's "Don't Worry (If There's a Hell Below)" to The Abbyssinians' "Black Man's Strain" to Public Enemy's "Fight The Power," countless black musicians have used music as a way to challenge racism and oppression. And these musicians have often received incredibly harsh criticism for doing so.

Many articles about pop music discuss the initial reaction of many white people to black musical forms. Nick Bromell, in his piece "The Blues and the Veil," discussed the negative reaction to early rock music, and Phinney does as well, in addition to discussing the reactions many whites have had to rap music. Many white cultural critics have dismissed rock as well as rap in the name of "morals," condemning these musical forms as being too sexual and immoral. It is completely possible to read these criticisms as being reflective of stereotypes that equate blackness with sexuality, and while I definitely think that argument is true, I also don't think it's the only factor involved. I would like to argue that these negative, racist responses are also a reaction to the political aspects of these musical forms, whether they are explicit or implicit.

I'd like to go back to the Phinney quote about how white people can "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo." Both rock and rap have threatened the status quo of white political power. With rap it's easy to see why; many of the most popular and influential rap songs have lyrics that are directly, explicitly critical of white hegemony. While the lyrics of early rock songs were in no way as explicitly political, there was still a political aspect to the popularity of rock music. Like jazz before it, rock was an originally black musical form that became popular among white people, which in itself threatened the white status quo (even though white people combated this by elevating Elvis to his popularity). It makes sense that the conservative (and sometimes liberal) white people who criticize(d) these musical forms would do so as a reaction to their threatened status quo, even if they used other reasons to justify their criticism. To phrase it differently, many of the white cultural critics who condemn black musical forms are afraid of the popularity of these forms and want to hold on to their power.

But where does nostalgia fit in to this discussion? Phinney also discussed how there has been a historical pattern of black people innovating a musical form and white people profiting off of it. While many black musical forms have had political origins, these forms have often lost their explicitly political meaning in the eyes of white America when they have been appropriated and turned mainstream. When music challenges whiteness it is obviously hard for white people to listen to it, and many white people have intense reactions to it. But when it is appropriated, transformed, and marketed to a new audience, it loses much of its political potency. Jazz and rock were originally condemned by the mainstream media, but are now part of it. And this is where I feel nostalgia plays a role.

Many people who have condemned rap music have also referenced the "good old days" of jazz or rock, completely unaware of their hypocrisy. I'd like to argue that the reason many white people are fixated on the "good old days" has everything to do with power. When rap started to come under fire from the mainstream media, rock and jazz had already been de-politicized. The "good old days" were referenced because there was a desire to hold on to music that had less political power than it used to, and less political power than more contemporary musical forms that had not been de-politicized. Again, we can see history repeat itself. When looking at music from a historical perspective, we can see a pattern that goes something like this:

Innovative and sometimes explicitly political black music becomes popular

A lot of white people condemn this new music (although white people are not always the only ones who do so)

This music is appropriated, commercialized, and de-politicized by other white people (as in the case of Elvis or Clapton)

Said music becomes mainstream

A new form of music appears, and the process repeats itself, with people lamenting the waning popularity of the music that used to be political and hated

To quote Stuart Hall, "This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion; the year after, it will be the object of a profound cultural nostalgia." You could also add "then it will be referenced in opposition to a new radical form."

In Kevin Phinney's piece "Souled American" there was a quote that really caught my attention:

"African Americans are more interested in discovering the Next Big Thing than in riding a fad past its relevance to daily life. Certainly there's no reason for black Americans to romanticize their experience here. This country hasn't provided any good old days for people of color."

Phinney then went on to discuss how white people "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo," and compared "white music" to "an old lamp," referring to its sentimentality and nostalgia. While I do think this is a bit of an over-generalization, I also think there is some truth to it. To understand why, it is important to discuss the ways in which black musical forms have political origins.

Many, many historically black musical forms have been political in some way. Rap is an obvious example, and it's also very easy to hear political sentiment expressed in reggae, soul, and even largely instrumental musical forms like jazz. And in all of the musical forms listed above, race plays a hugely important role in the musical politics. From Louis Armstong's "Black and Blue" to Curtis Mayfield's "Don't Worry (If There's a Hell Below)" to The Abbyssinians' "Black Man's Strain" to Public Enemy's "Fight The Power," countless black musicians have used music as a way to challenge racism and oppression. And these musicians have often received incredibly harsh criticism for doing so.

Many articles about pop music discuss the initial reaction of many white people to black musical forms. Nick Bromell, in his piece "The Blues and the Veil," discussed the negative reaction to early rock music, and Phinney does as well, in addition to discussing the reactions many whites have had to rap music. Many white cultural critics have dismissed rock as well as rap in the name of "morals," condemning these musical forms as being too sexual and immoral. It is completely possible to read these criticisms as being reflective of stereotypes that equate blackness with sexuality, and while I definitely think that argument is true, I also don't think it's the only factor involved. I would like to argue that these negative, racist responses are also a reaction to the political aspects of these musical forms, whether they are explicit or implicit.

I'd like to go back to the Phinney quote about how white people can "perceive black derived culture as threatening their status quo." Both rock and rap have threatened the status quo of white political power. With rap it's easy to see why; many of the most popular and influential rap songs have lyrics that are directly, explicitly critical of white hegemony. While the lyrics of early rock songs were in no way as explicitly political, there was still a political aspect to the popularity of rock music. Like jazz before it, rock was an originally black musical form that became popular among white people, which in itself threatened the white status quo (even though white people combated this by elevating Elvis to his popularity). It makes sense that the conservative (and sometimes liberal) white people who criticize(d) these musical forms would do so as a reaction to their threatened status quo, even if they used other reasons to justify their criticism. To phrase it differently, many of the white cultural critics who condemn black musical forms are afraid of the popularity of these forms and want to hold on to their power.

But where does nostalgia fit in to this discussion? Phinney also discussed how there has been a historical pattern of black people innovating a musical form and white people profiting off of it. While many black musical forms have had political origins, these forms have often lost their explicitly political meaning in the eyes of white America when they have been appropriated and turned mainstream. When music challenges whiteness it is obviously hard for white people to listen to it, and many white people have intense reactions to it. But when it is appropriated, transformed, and marketed to a new audience, it loses much of its political potency. Jazz and rock were originally condemned by the mainstream media, but are now part of it. And this is where I feel nostalgia plays a role.

Many people who have condemned rap music have also referenced the "good old days" of jazz or rock, completely unaware of their hypocrisy. I'd like to argue that the reason many white people are fixated on the "good old days" has everything to do with power. When rap started to come under fire from the mainstream media, rock and jazz had already been de-politicized. The "good old days" were referenced because there was a desire to hold on to music that had less political power than it used to, and less political power than more contemporary musical forms that had not been de-politicized. Again, we can see history repeat itself. When looking at music from a historical perspective, we can see a pattern that goes something like this:

Innovative and sometimes explicitly political black music becomes popular

A lot of white people condemn this new music (although white people are not always the only ones who do so)

This music is appropriated, commercialized, and de-politicized by other white people (as in the case of Elvis or Clapton)

Said music becomes mainstream

A new form of music appears, and the process repeats itself, with people lamenting the waning popularity of the music that used to be political and hated

To quote Stuart Hall, "This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion; the year after, it will be the object of a profound cultural nostalgia." You could also add "then it will be referenced in opposition to a new radical form."

Posted by

Jake

Sunday, October 25, 2009

5:41 PM

Road to Acceptance: Authenticity and Punk Rock

"You may think you’re the punkest sonofabitch in the state, but you’ve probably never even seen a real punk in the wild."

-Field Guide To North American Hipsters

When I was in 9th grade, like many other kids my age, I considered myself to be a punk rocker, even though, looking back, I knew next to nothing about punk at the time. I followed the path that a lot of my friends took, listening to blink-182 while I was in middle school until I heard the Ramones and immediately rejected "pop-punk" in favor of "real" punk rock (even though the Ramones' music is basically just 50s bubblegum pop with distorted guitars, and even though I never really gave up listening to Green Day). I remember one time I was on the bus and an older punk kid saw the Ramones shirt I was wearing and asked me "Do you even know who the Ramones are?" I said something along the lines of "Yeah, they're a punk rock band." Not satisfied with my response, still continuing to size me up, he asked me "What's your favorite song by them?" I immediately named some random Ramones song (I don't remember which one), and, seeing that I wasn't completely full of shit, he left me alone. Right afterwards, one of my friends whispered to me "Dude, he thought you were a poseur."

For its entire history, punk has always had a fixation on the "authentic," and I can't even count the number of discussions I've had where people have debated whether or not a band is "real" punk rock. Scholar Allan Moore noted this in his article "Authenticity as Authentication," saying, "In its direct opposition to the growth of disco, [punk] was read as an authentic expression." Moore barely begins to scratch the surface of this idea in his article, so I would like to examine it a bit further, using arguments about "authenticity" that Moore makes elsewhere in his piece.

First of all, Moore notes that "authentic" music is defined "by its ability to articulate for its listeners a place of belonging, in opposition to mere entertainment or those belonging to hegemonic groupings." While this quote comes from much later in the article than his quote about punk, I feel that the two quotes basically go hand in hand. We've all heard the punk rock narrative before: a teenager feels rejected by mainstream society, but discovers punk and soon finds an accepting community. I admit that as an angsty teenager I thought of myself as living out this narrative, even though I'm incredibly privileged, and even though I've never been anything more than a peripheral member of the punk community at my school or in my city. But the fact is that punk is viewed as a "place of belonging" by many people; that's why one of the main criticisms of punk is that the "non-conformist" punk movement is in many ways insanely conformist. In relation to Moore's comment about "mere entertainment" or "hegemonic groupings," I've also been in lots of discussions where I've condemned people who shop at Hot Topic or listen to Good Charlotte, because they're not part of the punk community and don't actually care about punk rock, they just listen to it for "mere entertainment" and belong to "hegemonic groupings." By condemning "inauthentic" punk rock, punks authenticate their lifestyle and separate "real" punks who belong to the community from poseurs who appropriate the style.

Moore also mentions how music is often viewed as "authentic" if it is "essential" to a specific subculture. This quote also directly applies to punk rock, which is a musical form that both grew out of and created an enormous subculture. This is one reason why people are attracted to punk in the first place: listening to punk allows people to become part of a subculture. This again relates to the idea of "authentic" music conveying a sense of belonging. And if we are to argue that "authentic" music is essential to a subculture, then punk may be one of the most "authentic" forms of music around. The word "punk" refers not only to a type of music, but also to a type of identity.

In addition, Moore argues that music viewed as "authentic" conveys "private but common desires," feelings that are personal to people, but that are also common. Again, the sense of alienation that is expressed in punk is without a doubt a "private but common" feeling, which, along and in conjunction with the previous two factors, allows punk to be referred to as "authentic" music.

Is this why there is a difference between "real" punk and "pop punk?" If we are to use Moore's arguments, pop punk is not viewed as being "in opposition to mere entertainment" or especially "hegemonic groupings;" it is not as "essential" to a specific subculture if it is produced by major labels and marketed to people outside of a subculture; and although it does convey "private but common desires," this may not be enough to make up for the other two factors, if we are to talk about perceived authenticity in these terms. This factor could also be why most pop punk bands are still given a little credibility, and are still allowed to be called "punk," even though it's with a prefix.

When viewing punk rock through Moore's arguments about "authenticity," it can be made clearer why some punk bands are viewed as "authentic" and other bands are not. This is one factor that draws so many people to punk, and one reason why people get into arguments about what is "real" punk.

Posted by

Jake

Sunday, October 11, 2009

6:47 PM

The Problems of Canonization

In 1994, scholar Harold Bloom proposed the idea of a literary "Western Canon," a collection of works that he deemed to be under fire by a so-called "school of resentment" represented by scholars who criticized the hegemony of classical European literature. Bloom's selection of works were ones that he considered to be important solely for their aesthetic qualities, rather than their social aspects. Bloom's ideas are what Taylor would likely describe as representative of modernist ideas of aesthetics; namely, that art should exist for art's sake, for nothing else other than beauty. The fact that Bloom chose to only label western works as being beautiful is on the surface entirely antithetical to the idea that social factors have nothing to do with aesthetics, but, as scholar Timothy D. Taylor shows, the viewing of western works as the most beautiful and aesthetically perfect is entirely consistent with the modernist view of aesthetics, which Taylor argues "strips everything of history, culture, and the social." Indeed, Bloom's views that European art forms are under attack are views that entirely ignore the history of colonialism, which put said western works on a pedestal in the first place.

It is not at all surprising that Bloom is an incredibly controversial figure, and that he is viewed as an elitist by many. But even if Bloom had never materialized his reactionary views into words, the idea of a literary canon has undoubtedly existed as long as the study of western literature has. I am certainly not the first person to notice similarities between academic ideas of literary canons and contemporary ideas of musical canons. For example, music critic Jim DeRogatis made a comparison between Bloom's western canon and contemporary music canons in his book Kill Your Idols, which is largely a criticism of commonly accepted musical canons. DeRogatis notes the connection between canons and nostalgia, arguing that the negative effects of nostalgia are often what inspire the creation of canons (this argument could be applied to Bloom's canon as well). However, rather than using this argument to attack canons of traditional "European music," as many other authors have, DeRogatis applies this argument to canons of rock music, which he sees as entirely antithetical to a musical form that was originally rebellious. DeRogatis argues in Kill Your Idols that nostalgia for the 60s among baby boomers has led to the creation of a rock music canon, which includes artists such as The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Rolling Stones, and that such a canon is just as elitist as Bloom's western canon or other scholars' notions of a European music canon.

Just to provide some more context, DeRogatis's argument is basically that the unofficial rock music canon as viewed by many people consists of "classic rock" bands from the 60s and 70s who were involved in some way in the hippie movement (indeed, the very term "classic rock" itself conveys the idea of a canon). When analyzing both the "European music" canon and the aforementioned rock music canon we can see many similarities. In fact, the rock music canon that DeRogatis describes and attacks is largely a European music canon, as bands such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, and Led Zeppelin are generally viewed as the most "aesthetically perfect" bands of this canon. Furthermore, in both examples of canons we can see how hegemonic these notions truly are, and how canons are used to serve dominant social groups. With some notable exceptions (Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana), members of the classic rock canon are generally white men, as are members of the traditional "European music" canon. It could even be argued that the rock music canon is even more problematic, since much of its repertoire is derived from African American musical forms, especially in the case of Led Zeppelin, who actually covered songs by African American musicians on their albums and credited themselves as the songwriters (I'll save my rants on Led Zeppelin for another time though). But on the other hand, as Taylor notes, many romantic composers derived their works from Other musical styles as well. So the European music canon and the rock music canon really aren't a whole lot different.

I'd like to apply this argument to a quote from scholar Philip Tagg that references Jimi Hendrix. Specifically, Tagg mentions the idea of how many music scholars would "laugh when you propose a Jimi Hendrix memorial guitar scholarship or suggest a series of workshops on the accordion… or try to start a course in Country and Western ensemble playing," but then goes on to say that "quite a few white European fans of ‘Afro-American music’ reading these lines would probably approve of the Jimi Hendrix scholarship but feel less sympathy for the accordion or C&W ideas…. [This] means that the most ironical effect of the twisted view of European music has been to perpetuate the rules of a ‘better-than-thou’ game in the field of musical aesthetics, so that even those of us trying to beat the ancien [sic] regime actually end up by playing the same game as our rivals, instead of changing the rules or moving to another sport altogether." While Hendrix does stand in contrast to the mostly white rock music canon, this quote still illustrates how "classic rock" has been canonized and how this is just as hegemonic as canonizing classical or romantic music. While many people who do canonize rock music probably think that they are rebelling against hegemony, in the process they are simply creating a new form of it. This is especially true since, as stated before, members of the rock music canon are largely white. True, the canon does include Jimi Hendrix, but he is definitely an exception. Can anyone think of any other black musicians who are frequently labeled "classic rock?" None of my friends could when I asked them, and I can think of way more examples of white people who are.

There is one point of disagreement I have with the above quote, but I also think that if Tagg wrote this article today instead of in 1989 he would have written it differently. Specifically, I would like to argue that while Tagg puts country music in opposition to classical music and classic rock, recently a canon of country music has been emerging. Many contemporary musical elitists are beginning to put country music onto a pedestal, just like people did with rock music before. In fact, the people who are currently creating a country music canon probably think they are doing so as a rebellious act as well. If you don't believe my argument about country music, I'll just mention that I work as a monitor in the music building at my school and one of the genres I hear the most is bluegrass, played by students presumably because of its perceived authenticity. While the creators of this country music canon may have rebellious intentions, just as the baby boomers did before them, we can see from the latter example that canons are inherently un-rebellious, since instead of dismantling cultural norms they simply change them slightly.

Posted by

Jake

Saturday, September 26, 2009

4:27 PM

Cool Thing Of The Week: Windows 7

So yea, I migrated from XP to Windows 7 (64 bit) today. It took about 2 hours, and so far I have to say that I'm pretty impressed. It's damn snappy, boots up faster than XP ever did, and is full of little touches that become second nature very quickly.

I've also got to say that I have had some compatibility issues with some older hardware (an ancient pci ethernet card that stopped being supported in 2006) but a suprisingly pleasant time otherwise. So far I've yet to run into any hiccups or really any issues at all.

I'm sure a lot of this has to do with the hardware upgrade - I got 4 GB of ram super cheap over labor day weekend, bringing me to a total of 6 GB. I also installed it on a 10,000 RPM HDD, so you could attribute some of the speed increases to hardware.

You could, that is, until I told you that I'm dual booting XP and 7, and that they're both playing nice. For anyone that's ever used a Microsoft OS, that will be a bit of a shock. MS never really liked supporting dual booting all that much, but the 7 installer make it extremely simple.

So basically, 7 shows Microsoft doing a lot of things right - a focus on performance, finally accepting that some people might want more than one OS on their system, and far fewer resources consumed than Vista. It's the 98SE/ME/XP saga all over again.

So yea, I migrated from XP to Windows 7 (64 bit) today. It took about 2 hours, and so far I have to say that I'm pretty impressed. It's damn snappy, boots up faster than XP ever did, and is full of little touches that become second nature very quickly.

I've also got to say that I have had some compatibility issues with some older hardware (an ancient pci ethernet card that stopped being supported in 2006) but a suprisingly pleasant time otherwise. So far I've yet to run into any hiccups or really any issues at all.

I'm sure a lot of this has to do with the hardware upgrade - I got 4 GB of ram super cheap over labor day weekend, bringing me to a total of 6 GB. I also installed it on a 10,000 RPM HDD, so you could attribute some of the speed increases to hardware.

You could, that is, until I told you that I'm dual booting XP and 7, and that they're both playing nice. For anyone that's ever used a Microsoft OS, that will be a bit of a shock. MS never really liked supporting dual booting all that much, but the 7 installer make it extremely simple.

So basically, 7 shows Microsoft doing a lot of things right - a focus on performance, finally accepting that some people might want more than one OS on their system, and far fewer resources consumed than Vista. It's the 98SE/ME/XP saga all over again.

Posted by

Bobbicus

Friday, September 11, 2009

8:59 PM

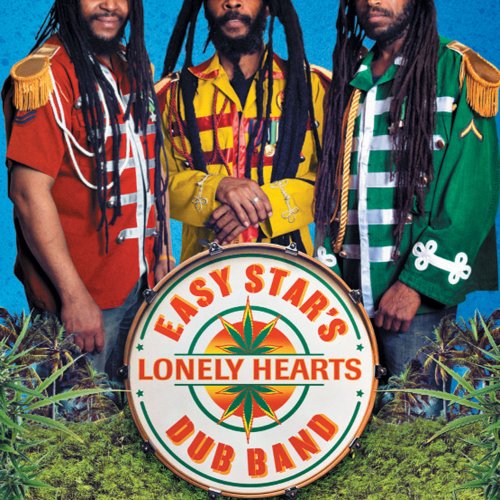

Belated Album Review: Easy Star's Lonely Hearts Dub Band (Also, why I don't like Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band)

Anyway, tribute albums usually suck, so while I didn't particularly like Radiodread, I wasn't disappointed by it, since I didn't expect to like it in the first place. For that reason, I was pleasantly surprised by Lonely Hearts Dub Band.

Now, just for a little background information, I don't like the album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band by the Beatles. I think it's one of the most overrated albums of all time, mainly because it's all over the fucking place musically. It's a concept album with no concept. The band starts out by introducing themselves as an imaginary band, which is a pretty cool idea, but then they just drop acid around track 3 and forget about the concept entirely. By the middle of the album they start introducing a magical kite and bastardizing Indian music and we have absolutely no idea what the fuck is going on. I've heard tons of hippie assholes tell me that the album's so cohesive, which is bullshit. We have a sitar song next to an old-timey woodwind ensemble one. How the fuck is that cohesive? I've also seriously heard people say "man, Sgt. Pepper is so great! It's got all the classics on it, like Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane." (Those songs are from Magical Mystery Tour, which is my favorite Beatles album, because it's cohesive and has all the classics on it.) And don't even give me that bullshit about how it's better when you're stoned, because all music is better when you're stoned. Why do you think dub music has an audience? Using that argument is like saying "Don't say McDonald's tastes bad, it's better when you're hungry." Of course Sgt. Pepper sounds incredible stoned, but an album that's actually good will sound even better! Sgt. Pepper is also proof that people don't necessarily make better music when they're on drugs. Frank Zappa did way cooler shit in the 60s, and he never smoked weed in his life. If Frank Zappa had done drugs, he probably wouldn't have recorded Uncle Meat and would have wrote something shitty like "Good Morning Good Morning" instead.

Anyway, I don't like the Sgt. Pepper album. If you want to read more about why it sucks, read this fantastic piece by Jim DeRogatis. Also, just to clarify, some bands, particularly They Might Be Giants, have made exquisite albums that have absolutely no musical consistency. They're a band who knows how to pull that off. The Beatles never were. That's why no one ever listens to the white album all the way through, and if you say that you don't skip "Revolution 9" you're a pretentious asshole.

Anyway, the fact that I don't like Sgt. Pepper probably made me like the reggae version of it way more, even though I love OK Computer and didn't really like its reggae version, which is strange, but also kind of makes sense. Since I love OK Computer, I didn't really want anyone messing with its songs (except of course for Toots & The Maytals. They can mess with any song they want as far as I'm concerned. Everything they touch turns to gold). On the flipside, I don't like Sgt. Pepper, so I like the fact that someone is actually making it's songs good. Now to be fair, the original album does have a lot of good songs on it... oh, wait, I checked the track listing, and it actually only has one really good song on it: "A Day In The Life," which, despite how I feel about the album, is my favorite Beatles song ("Eleanor Rigby" and "Happiness is a Warm Gun" round out my top 3. I guess I like all the morbid, depressing Beatles songs). But still, not all of the songs on the album are bad. Sure, "Within You Without You" goes on for way too long and is just George trying to recreate "Norwegian Wood" and "Love You To," the Beatles were on way too much acid when they wrote "For The Benefit of Mr. Kite," and "Good Morning Good Morning" just sounds like a cartoon exploding, but all of the other songs on the album are solid and just suffer from this lack of consistency. But the great thing is that Lonely Hearts Dub Band solves this easily. It's impossible for a reggae album to suffer from a lack of consistency. The only thing a reggae album can suffer from is too much consistency.

LHDB really shines because it makes the entire album consistent and really allows the actual songs to shine, rather than get covered up by bizarre, self-indulgent production. The other thing that's great about it is that it has fucking amazing guest artists on it. The track listing reads like a list of reggae all stars. We have The Mighty Diamonds, Max Romeo, Ranking Roger, Steel Pulse, U-Roy... shit, everyone on this album is fucking incredible. So now it's time for the song by song review process! (BTW, you can listen to the whole album on youtube, so I'll be providing links to each song.)

The first song essentially serves the same purpose as it does on the original album: just an introduction. It's not particularly exciting, but then again, this song never was the high point of the original album either (that might be another reason why the original suffers: it has a weak opener). The next track, Luciano covering "With A Little Help From My Friends," is a million times better than anything Ringo has ever done, including drumming for the Beatles (ok, I admit that was a little too harsh). The original version of this song just kind of lumbers along and has no passion in it, but Luciano's version manages to be both upbeat and mellow, and has terrific vocals.

Next we have "Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds," which I will henceforth be abbreviating as "LSD." I've thought for a while that LSD would make a great reggae cover; I always imagined it starting out with just a sick descending bassline and some phenomenal reggae singer doing the first verse over it, and then you'd hear a pickup of high-pitched snare drums before the chorus, which would be upbeat and full of sound. This version pretty much starts exactly how I imagined it, but I think the drums come in way to early. Still, it's pretty cool. Frankie Paul is great, especially when he changes the lyrics a little to include a reference to the Ethiopian flag (cellophane flowers of red gold and green...). Still, I think the song should speed up a little more at the chorus. But that minor complaint doesn't keep this from being an awesome cover.